Credit derivatives

Key concepts

Credit derivatives are instruments whose value is derived from that of an underlying bond, loan or other credit agreement. They are used to assume or lay off credit risk in isolation from other types of risk. The two main instruments are credit default swaps and total return swaps and they:

- enable holders of credit risk, such as banks, to lay off the credit risk in their loan, bond and derivatives portfolios without having to sell the underlying credits upon which their relationships may be based. This makes true credit portfolio management possible.

- are an alternative to asset swaps for institutions unable to buy high-quality assets for funding cost reasons, or unable to access the loan markets directly, to gain their desired credit exposure on an unfunded basis (or, if embedded in credit-linked notes, on a funded basis.)

- provide a mechanism for BIS capital management as they allow banks to remove assets from their balance sheets particularly at key time regulatory capital requirements for banks are often calculated on peak credit exposure at the end of reporting periods and can attract lower regulatory capital than the cash equivalent.

- allow synthetic assets to be created that do not exist in the markets.

- allow hedging of contingent credit risks embedded in assets hedged with currency swaps.

- allow corporates to hedge the credit exposures they have to other corporates via trade receivables and long-term purchase contracts and to their banks via long term trade financings, loan facilities such as revolving credits and swap and option portfolios.

- allow corporates and banks to hedge against emerging market risk where guarantees are not available or export agency cover is expensive.

- create a link between the bank and insurance markets vastly increasing the capacity of both to absorb credit risk. In sectors where corporate demand for insurance is so great that there is no more reinsurance capacity, insurance and reinsurance companies can use a default swap to go short the default risk of a basket of credits issued by entities in that sector so freeing up their lines in that sector. See chapter 16 for: credit-linked notes credit-spread linked notes, first to default bonds, repackaged notes, sovereign default notes

Definitions

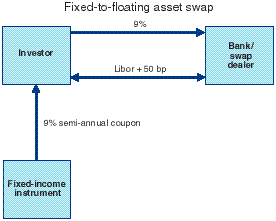

asset swap

A transaction which transforms the cashflows of a security through the application of one or more swaps. For example, bond coupons can be swapped from fixed to floating rate or vice versa; interest and principal can be swapped into a different currency; the yield from a security can be swapped for a cashflow based on an index in another asset class. An asset swap transaction involves three distinct steps: an asset is purchased for cash; the cash flows are swapped into the desired form; the package consisting of the asset and the swap(s) is held by the investor these are on-balance sheet items.

The most common type of asset swap is the par asset swap. Here the notional amount of the swap is equal to the face amount of the underlying asset. The asset is purchased for par and the investor receives par at maturity. The other vanilla asset swap is the market value asset swap. Here the notional amount of the swap is equal to the market value of the underlying asset at the time the trade is executed. See repackaged securities for an explanation of the link between vanilla asset swaps and true credit derivatives.

A number of important variations allow for more tailored transactions. Callable asset swaps and step-up callable asset swaps are used where the underlying asset is either callable or step-up callable. The swap matches the coupon and callable features of the underlying. They are also used in convertible asset swaps (also known as stripped convertibles/converts).

Here the underlying asset is a convertible bond. Typically a bank purchases a convertible and sells it to an investor for its fixed-income value. The investor then enters into a swap the asset swap with the bank exchanging the fixed-rate coupon payments on the convert for a floating rate. The swap agreement also contains an option giving the bank the right to call the bonds back at any time and so terminate the agreement (hence the asset swap is callable). The investor effectively holds a callable floating-rate note backed by the credit of the convertible issuer. He has given up the equity option embedded in the convertible the option has been ‘stripped’ from the convert in return for a higher spread on the swap. The bank now owns the equity component of the convertible as it can call the bonds to extract any appreciation in the value of the equity option.

Callable and puttable asset swaps are also used to take views on changes in credit spreads they are sometimes viewed as the first credit derivatives and in this context are often referred to as credit spread options (see below). Other structures include cross-currency asset swaps in which the coupon of the asset is swapped into a different currency; forward-[starting] asset swaps which can be used by investors wishing to take advantage of a steep credit curve for a specific issuer. These are also known as knock-out asset swaps as if the underlying asset defaults before the start date of the swap, the forward swap is cancelled; maturity-shortened asset swaps where the maturity of the swap is less than that of the underlying asset; and asset swaps can be combined with other options, such as caps, floors and collars, to give more tailored payoff profiles. See also switch asset swap .

Contingent credit risk

Indirect credit risk such as that embedded in assets hedged with currency swaps.

Example

The arrangers of bond repackagings face contingent credit risks. Suppose a bank can buy Brazilian Brady bonds cheaply in the US market but cannot sell them into Europe because of their unusual floating coupon and amortization schedules. It places them into a special purpose vehicle (SPV) and swaps them into fixed-rate Deutschmark bullet bonds. The underlying bonds are placed in a trust and swapped using a cross-currency swap. Most SPV structures have triggers that force early redemption of the new bonds and the unwind of the SPV in the event that collateral levels fall below predetermined thresholds.So, if credit spreads rise, or in the extreme the bonds default, the swap has to be unwound as the structure is dismantled. If the dollar strengthens against the Deutschmark the bank will lose money on the swap unwind. In an extreme case, the residual value of the bonds may not be enough to cover the shortfall, so there is a credit-related contingent foreign exchange risk. To cover this risk, the arranger could take out default protection on the underlying securities.

Similarly, banks run a quanto credit risk when cross currencies in an asset swap. For example: a bank takes a dollar-denominated asset and swaps it into yen using a cross-currency swap. If the underlying asset defaults and the swap is unwound there will be a windfall gain or loss on the swap. Bankers recall deals when USD/JPY traded at 250 that, if they defaulted at today’s exchange rate, would incur windfall losses as large as the bond principal. One way to hedge is to take credit exposure in dollars and buy credit protection in yen. But the size of this hedge must be managed dynamically in the same way as the risks embedded in quanto instruments.

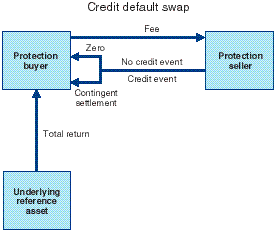

[Credit] default swap

A swap agreement in which one counterparty (the protection buyer, risk seller, hedger) pays a fixed periodic fee, usually expressed in basis points per annum on the notional amount, in return for a payment by the other counterparty (the protection seller, risk buyer, investor) contingent upon a specified default event relating to an underlying reference asset (a loan, bond, stream of trade receivables or derivative contract cash flows). While there is no default event, the protection buyer pays the swap counterparty the periodic coupon. If the specified credit event occurs there is an exchange of cash flows and/or securities designed so that the net payment to the protection buyer mirror the loss incurred by creditors of the reference credit in the event of its default. This exchange of cashflows usually follows one of three patterns depending on the liquidity and availability of the reference securities:

- Physical delivery: the protection seller pays full notional amount in exchange for defaulted reference securities

- Cash-settled recovery value-linked payment: the protection seller pays the counterparty an amount calculated as the fall in the price of a reference security below par after default as established by polling reference dealers. So a typical cash settlement formula would be [(par – recovery value) x notional principal of swap]. The price of the reference asset can be determined either as an average determined over a three-month period or via a single poll.

-

Cash-settled binary payment: the protection seller pays the counterparty a predetermined fixed amount or pre-determined percentage of notional is payable. This structure is sometimes known as a digital credit swap. Because they are difficult to price and hedge digital credit swaps command a premium most hedgers consider too expensive. The economic effect of the transaction is to allow the holder of an exposure to a particular counterparty to transfer the risk of that counterparty’s default to a third party without transferring the underlying asset itself. The third party the protection seller assumes the credit risk of the exposure in exchange for the return from it and so generates investment income with no funding costs. Credit default swaps with the same maturity as the underlying asset are equivalent to the underlying asset but with the interest rate risk immunized. That in turn means that they are the same as total return swaps (see below) with the interest rate risk immunized. Hence the pricing is directly comparable to asset swaps.

The periodic coupon is generally derived from the Libor spread received by an investor in the underlying obligation in the cash or asset swap market. The asset swap market spread is the benchmark because the default swap is an unfunded transaction. To replicate it in the cash market would require an investor to borrow the underlying bond through the repo markets. On average, repo financing for high-grade corporate assets is available at Libor flat, so the investor’s spread on the trade is a spread to Libor. This arbitrage, where it is available, constrains the pricing of default swaps.

However, hedgers generally have to pay a premium to this Libor spread depending on the tenor of the swap and the liquidity of the underlying bond. The swap is generally less liquid than the underlying, which means investors demand more for taking the swap than they would the bond. On the other hand, as the transaction is unfunded, it gives institutions with high funding costs access to assets they would not normally be able to purchase without incurring negative carry. Default swaps are also often structured with maturities different to that of the underlying exposure. This creates synthetic investments that are not available in the cash markets. Both these factors can make the swap more desirable than a cash investment and drive the price down. In addition, in a credit default swap the protection buyer has a credit exposure to the protection seller contingent on the performance of the reference credit. If the seller defaults, the buyer must find alternative protection and will be exposed to changes in credit spreads since the inception of the original swap. So protection bought from higher-rated counterparties should command a higher price. Also, the protection buyer must also take into account the correlation between the risk of default of the seller and the hedged exposure. If there is a positive correlation, then default by the underlying borrower may imply that the swap counterparty’s ability to deliver the notional value of the reference security is impaired. At worst this might means that the reference credit and protection seller default simultaneously in which case the buyer is unlikely to recover the full default payment due.

Credit default swap maturities usually run from three months to 10 years and transaction sizes range from USD5 million to USD300 million. Bid/offer spreads range from 50bp to 150bp. The main participants in the market are banks. Also known as a credit swap, and also, particularly if instead of paying a periodic fee the protection buyer pays a one-off upfront payment, as a [credit] default option. Strictly speaking though, since the swap contains no optionality, it is not a true option.

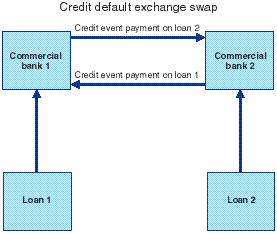

Credit default exchange swap

A type of default swap in which investors swap the default risk of one asset or basket of assets for that of another. Each party serves simultaneously as a protection buyer and a protection seller. These swaps are used mainly by commercial banks who want to hedge concentration risk in their loan portfolios in a single unfunded transaction without buying and selling packages of commercial loans.

Example

An investor seeks exposure to a loan yielding libor + 350 basis points that a double-A rated bank has made to a Turkish corporation. The investor enters into a total return swap with the bank – the total return payer under the terms of which it pays three-month Libor +100 basis points and receives Libor + 350 basis points plus or minus any change in the market price of the loan. If the loan’s market value remains unchanged over the life of the contract, then the investor earns 250 bp on the transaction. However the investor bears both the price risk and any early repayment risk on the loan over the life of the agreement.

Credit spread

The yield of a security or loan less the yield of a corresponding risk free security. Plotting credit spreads the premium over the benchmark against bond maturity produces the credit curve for a borrower. In theory this margin compensates investors for the risk of default. In practice it is also affected by liquidity considerations and and number of other market factors. Credit spreads can be traded with credit spread forwards and options. The key variables in trading are the term structure and volatility of credit spreads. The forward credit spread is calculated as follows: the forward prices of the security and the risk free benchmark are calculated and converted to the corresponding forward yield. The forward credit spread is the forward security yield less the forward risk free rate.

In theory the credit spread should increase in line with increasing default risk and maturity. In practice, forward credit spreads increase in the case of a positively sloped yield curve but do not seem to reflect investor expectations. Forward credit spreads appear to be a poor indicator of future spot spreads and seem relatively more volatile than the underlying securities. This higher spread volatility reflects the absolute lower level of spread and the imperfect correlation between the yield on the security and the risk free rate.

Credit spread forward

Equivalent to a forward asset swap these are forward-starting transactions which enable credit spread trading/hedging at a future date. Credit spread forwards allow counterparties to express views on future credit spreads and benefit from a narrowing or widening of the credit spread between debt instruments. One application is therefore for borrowers wishing to lock in future borrowing costs without inflating their balance sheet today. In the case of a borrower hedging issuing costs the reference credit would also be the protection buyer which significantly increases the counterparty risk to the protection seller. Collateralization is being used to mitigate this risk.

Example

An investor wants to take advantage of steep forward credit curve by locking in wider spreads in the future than are available today. He identifies an eight-year emerging market bond that currently trades at Libor+70bp. Three-year bonds from the same issuer trade at 30bp over. At current market prices, by agreeing to buy the eight-year asset in three years’ time an investor will lock in Libor plus 95bp for the remaining five years of its maturity 25bp more than eight-year assets today. The risk for the investor is that the issuer’s credit fundamentals deteriorate over the the next three years and spreads widen by more than 25bp. However, the downside is limited by the fact that if the issuer defaults in the next three years then the investor does not have to buy the asset.

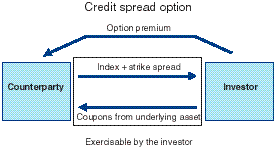

Credit spread option

Credit spread options are calls (puts) on a credit-sensitive asset with at a pre-determined strike price expressed as a spread to an index typically Libor or to government securities. They allow buyers to buy or sell the underlying asset at a pre-determined price for a pre-determined period of time. The buyer of a credit spread call profits if spreads tighten. The buyer of a put profits if spreads widen. The options are priced off the credit curve, expected credit spread volatility and expected recovery rates.

The reference asset is usually either a floating rate asset or a fixed-rate asset swapped into floating rate through an asset swap. Floating-rate reference assets are favoured because the floating coupon immunizes interest rate risk any change in the principal value of a floating-rate asset is largely due to changes in credit perception. This means that, in general, credit spread derivatives such as forwards and options are equivalent to forwards and options on an asset swap.

So, for example, a put seller would be put into an asset swap paying par for the asset. The seller would then pay the coupons on the asset and in return receive the pre-determined spread over the Libor (the strike spread). Because of this, credit spread options are equivalent to callable or puttable asset swaps and are sometimes known as asset swaptions.

Asset swap buyers can use these options to enhance yield by, for example, selling calls. This exchanges upfront premium income against the loss of upside if spreads tighten. Investors can also use combinations of calls and puts to lock in a current spread and transactions can be structured that allow investors to go long or short the spread between two different assets say two countries’ sovereign debt or benchmark corporate bonds of different ratings or sectors. Institutional investors are now using credit spread options to slice up a credit into different tenors. A sophisticated credit risk player might buy a five-year bond and sell the first two years as a way of rolling down the credit curve.

Basket/portfolio spread options are also available in which the option is written on a basket of reference credits rather than just one. For example, in a basket credit spread put trade an investor increases its premium income by selling a number of puts, each linked to a particular security at a particular strike spread. The buyer has the right to exercise the seller into any one of the reference assets at its strike spread, in the full notional amount.

Example

Improvements in economic fundamentals in Hungary have created new credit lines. In the Asian credit crisis five-year paper went from 35bp over to as wide as 100bp. Spreads are now back at Libor + 40bp but some expect a retreat in the short run. An investor with a price target of Libor + 50bp can utilize its new credit line while waiting for prices to move to its entry level by writing one-year put options struck at the target spread. Typical terms would be that the investor receives 25bp running yield for giving the option counterparty the right to sell it bonds at the target spread. The income requires no balance sheet and no funding requirements. If the spread remains below Libor + 50 bp the investor has earned a premium of 25 bp multiplied by the notional principal of the contract which it can use to buy the bond at a price below market (if it wants). If the spread has risen above the target level then the option seller exercise their option to sell the bond at the strike spread and the investor buys the bonds at its strike spread plus the premium which is the originally targeted level. Alternatively the investor can settle the trade by paying the option seller the notional principal of the contract multiplied by the difference in basis points between the final spread and the strike spread. The higher the strike spread is above the current spread of the reference asset, the more the credit spread put resembles a credit default swap in which the investor pays a small periodic fee to buy protection against a large downward move in the price of the reference asset.

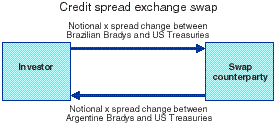

credit spread exchange swap

A swap in which counterparties swap the credit spreads of two reference securities. This allows them to take views on the relative spread between two comparable credit-sensitive securities.

Example

An investor wants to monetize the expectation that the credit spreads of Brazilian Brady bonds will narrow relative to those of Argentine Brady bonds. The investor chooses a spread exchange swap structure that produces a pay-off tied to the difference in the spreads of two Brady bonds. The trade uses the exchange of two absolute spreads pegged to a US Treasury to to capture the relative spread of two reference securities. the investor pays the dealer the notional amount multiplied by the credit spread between the Brazilian Brady bond and the US Treasury. In exchange, the dealer pays the investor the same notional amount multiplied by the credit spread between the Argentine Brady and the US Treasury. If the credit spread of the Brazilian bonds falls relative to that of the Argentine bonds , then the investor receives a payment from the dealer and vice versa. This kind of trade is normally structured so that no payment is made unless a change in the relative spread occurs.

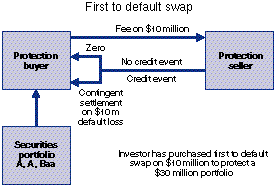

First to default/basket default swap

A default swap in which there is not one but a basket of reference assets. The protection buyer pays a fixed periodic payment, usually expressed in basis points per annum on a predetermined notional principal.

The protection seller makes no payments unless some specified credit event relating to any one of the reference securities in the agreed portfolio occurs in which case the protection seller is obligated to make a payment based solely upon the defaulted security. In other words, the swap only pays out on the first default which occurs in the basket. Other defaults are not hedged. The investor receives a return approximately equal to the spread of the worst names in the basket plus an additional correlation dependent spread for each of the other names in the basket. The additional spread is based on the commitment fees on unfunded loans for those names.

These transactions started off with six or so reference assets and banks are now executing $1 billion-plus default swaps on a basket of between 30 and 50 credits. These larger deals are essentially the same as a privately placed unfunded collateralized loan obligation. This type of synthetic securitization has two key benefits over standard CLOs or credit-linked notes. First, it is cheap: because it is unfunded it allows a strong bank to maintain its sub-Libor funding spread. Second it is extremely flexible: as the assets remain on the banks balance sheet rather than being having to be transferred from different branches or legal entities into a special purpose vehicle which can cause internal, regulatory, legal and tax problems.

First to default swaps generate much higher returns than through a single investment in any of the other names. As long as the basket is diversified, the hedging institution lays off exposure more cheaply than hedging the names individually. Also known as basket/portfolio (credit) default swaps.

Market contingent credit derivative

Credit derivatives whose payout depends on the mark-to-market value of an underlying credit exposure and is contingent upon that value being negative. A hedger would determine its maximum expected exposure on a credit or group of credits (these could be securities or derivatives positions) if those credits were to default. It would then enter into a market contingent credit derivative with a notional amount equal to this exposure. The hedger pays a commitment fee say 15bp on the notional amount of the agreement unless the mark-to-market exposure on the interest rate or currency position becomes negative. In that case the institution pays the full hedging cost of the reference party but just on this negative amount. In the case of default, the buyer of the hedge would have protection equal to the unwind value of the underlying position. This is much cheaper than using a standard credit derivative because the hedger only pays for credit protection when it is needed when the mark-to-market value falls below zero. If the mark-to-market value remains positive, then the commitment fee paid will typically be around half the cost of fully hedging the underlying credit risk. See swap guarantee.

Mark-to-market cap

An interest rate hedge structure that puts an upper limit on the mark-to-market loss of a swap or a swap portfolio. The portfolio version gives the client to enter into a portfolio of offsetting swaps at any reset period over a chosen period, at strikes that ensure that the mark-to-market loss will not exceed a predetermined amount. The premium depends on the underlying parameters of the swap portfolio: tenors, notional amounts, strikes, correlations and embedded option features. Protection on a portfolio basis is cheaper than buying caps on the individual swaps.

Example

A corporate treasurer may have a series of interest rate swaps on his books, hedging a variety of underlying debt obligations. This treasurer was previously not required to mark his swaps to market, but recent accounting changes force him to. In this case, he wants to limit any adverse bottom line effects. Suppose he has a portfolio of five receive-fixed swaps maturing at different dates between October 1996 and October 1998 which currently show a mark-to-market loss of $4 million. A mark-to-market cap would provide the company with an option to enter into pay-fixed swaps at any rate reset date over the next 12 months exactly offsetting the existing swaps in the portfolio and locking in a loss of $4.5 million. Alternatively the options could be cash-settled. The cap premium can be paid upfront or on a periodic basis.

Recovery rate

The percentage of par paid to creditors after a default. This is an important concept in credit derivatives because it can dictate the pricing and structure of a number of products.

Example

One bank is willing to take exposure to a credit at the senior unsecured level at a spread of 40bp. Another bank with this existing exposure is willing to sell this exposure at the same spread. However, the first bank considers the likely recovery rate for the credit to be 50% while the second thinks that it is 70%.

The two institutions may enter into a credit swap in which the contingency payment is fixed at 50%, rather than at the floating recovery rate of senior unsecured debt as determined by dealer poll. The second bank, the protection buyer, is prepared to pay up to 40 x 50/30 bp (67bp) for the fixed recovery contract since it offers more protection than the floating recovery contract given the bank’s recovery rate expectation of 70% (50/30 is the ratio of expected losses in the fixed versus floating recovery transaction). Conversely, the first bank is happy to receive any premium over 40bp for the 50% fixed recovery transaction since in its view this is equivalent to the floating recovery transaction. A transaction completed at, say, 55bp, would leave both institutions happy given their divergent recovery rate views.

Reference asset

The underlying assets on whose price or status a credit derivative is based. Reference assets can take almost any form including government bonds, Brady bonds, Eurobonds, MTNs, loans,.letters of credit, trade receivables, receivables due under derivative agreements, CBOs, mortgages, indices and funds.

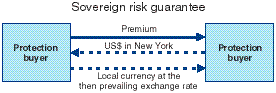

Sovereign risk guarantee [option]

An option that gives the holder the right to demand delivery of a pre-determined amount of hard currency to a bank account in a country with no exchange controls in exchange for the local currency of a particular sovereign at the prevailing exchange rate in the event of a pre-determined credit event. This event is usually defined in terms of foreign exchange controls or non-convertibility.

Sovereign risk guarantees are used to hedge a counterparty’s business risk in a country rather than investment risk in a security. Countries can suspend foreign-exchange convertibility without defaulting on any specifiable reference asset. This makes credit swaps imperfect hedges against many forms of sovereign risk. Even though the imposition of currency controls would likely lower any sovereign borrower’s credit standing in investors’ eyes, which would increase the value of a credit swap, the basis risk would be too large to make the hedge usable. The sovereign risk guarantee lets the protection buyer transfer money out of a country even if it has declared non-convertibility or non-transferability.

The protection seller may simply be an institution that wishes to be paid a premium for assuming non-convertibility risk. However they can also be entities such as local banks or local or foreign corporates who need local currency regardless of convertibility. In particular, corporations that have entered into joint venture agreements that specify local investment at specified future dates could write sovereign risk options against an underlying position to gain a premium.

The options are priced off the sovereign’s outstanding hard currency obligations of the same tenor as this is the investment alternative and carries equivalent risks. The option will be more expensive because it is illiquid. Transaction sizes typically range between USD5 million and USD20 million with tenors up to 12 months. These products are almost always embedded in short-dated credit-linked limited recourse notes. These are denominated in hard currency but pay out in local currency if specified credit events occur (see chapter 16).

Structured repo

Flexible repo agreements that create financing and investment vehicles that are more efficient than those available in the traditional repo market. Investors can use cancellable repos and convertible repos to set initial financing rates well below those available on the plain vanilla market. They can also achieve better risk-adjusted returns by using reverse structured repos to hedge credit risk on emerging market bonds.

Example

An investor can achieve collateralized above-market, double-A rated returns using a reverse structured repo to finance a single-B rated Ecuadorian sovereign bond for a double-A rated bank counterparty. The investor pays cash for the bond at the trade date and at maturity it resells the bond to the bank at par. In the interim the investor holds the bond on its balance sheet for a year and earns superior risk-adjusted returns by exchanging the credit risk of the single-B rated bond for the double-A rated counterparty risk of the bank counterparty.

Swap guarantee

A credit swap whose notional principal is adjusted in line with the mark-to-market value of a reference swap (or other market sensitive instrument) and with a contingent payment triggered by default on that swap. The main use of these products is to manage credit risk in cross-currency swap portfolios.

The problem swap counterparties face is that the projected exposure on a swap can vary enormously throughout the life of a swap. Take a 10-year $100 million notional yen/dollar currency swap with principal exchange initiated in May 1990. At inception, prevailing rates implied a maximum exposure at maturity of $125 million. five years later, as the yen strengthened and interest rates dropped, that maximum exposure had risen to $220 million. Three years’ later and it has fallen again by almost $100 million. This exposure is exacerbated if the counterparty’s credit quality is correlated to the level of the yen and/or to interest rate movements. A lender in a currency that has experienced depreciation and rising interest rates will be out of the money on the swap and could be a weaker credit.

The swap guarantee hedges the exposure between margin calls on collateral posting. Alternatively it can be structured to cover any loss beyond a pre-agreed amount. The buyer will only incur default losses if the swap counterparty and the protection seller default. This means that the credit quality of the buyer’s position is compounded to a level better than the quality of either of its individual counterparties.

Switch[able] asset swap

An asset swap in which the buyer sells a counterparty (usually the dealer from whom the asset swap was bought) the right to substitute the underlying asset with another asset (or any one of a basket of pre-specified assets) on particular dates usually at a spread higher than the prevailing market level. The embedded option is a spread option between the substitutable securities.

At the initiation of the transaction all the underlying assets will be of the same duration and credit quality and so ought to move together in price with changes in interest rates. The main reason for any spread change is therefore due to a change in perceptions of credit quality. The counterparty exercises his option to substitute if one of the basket declines in credit standing versus the asset that is asset swapped at the beginning of the transaction. These swaps are used to enhance the yield of vanilla asset swaps. Also known as a basket asset swap. See basket credit spread option.

Example

An investor with a funding cost of Libor+10bp wants to buy an asset swap trading at Libor+10bp. It sells an option under which it agrees to deliver the Libor+10bp asset to the counterparty in return for another asset. This asset is either the cheapest to deliver from a basket or is a pre-specified security. In the latter case, the counterparty can deliver the new asset at a spread 15bp worse than the prevailing market level. The premium received for the sale of this option is 10bp. The investor receives enhanced yield in return for the credit risk on the new asset. The option buyer has hedged for less than the cost of a standard default swap.

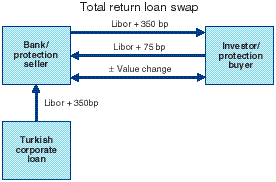

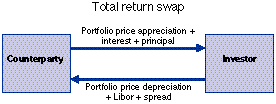

Total return swap

An agreement that allows a counterparty to transfer the total economic risk both credit risk and market risk of an underlying asset or portfolio of assets to another counterparty without transferring the asset itself. (A default swap transfers only credit risk to the counterparty.) The holder of an asset wishing to hedge exposure to that asset pays the total return (all interim cash flows and any change in positive mark-to-market value) of a reference asset and (usually) receives Libor plus a fixed spread and any capital depreciation from the other counterparty. Price appreciation or depreciation may be calculated and exchanged at maturity or on an interim basis. Total return swaps can be cash settled on the basis of a final mark-to-market value of through physical delivery at maturity in which case the total return receiver pays the previous mark-to-market price of the asset or portfolio in exchange for the actual securities. Eligible assets are those with liquidity and observable prices.

Pricing depends on a number of factors: the cost of funds for the short counterparty; balance sheet constraints the short counterparty may have the assets on its balance sheet with the associated capital charges; credit risk both the riskiness of the asset as well as that of the long counterparty are considered. Several methods can be employed to mitigate the risk of the transaction including triggered collateral accounts, up front buffer collateral accounts and daily mark-to-market.

As with the credit default swap there is no exchange of principal and ownership and funding of the underlying asset is unchanged. If the swap maturity matches that of a reference loan or bond asset it is simply a synthetic version of the bond or loan that allows the holder to go long or short easily and without funding. If it is not, then the swap is a synthetic asset that may not exist in the market.

Total return swaps can be structured on all the same asset classes as other derivatives. They are used by investors to go long or short securities or instruments that are difficult to obtain, that they cannot purchase in the form in which they are traded in the cash market or whose form is too complex for them to analyze. They also offer unfunded so leveraged exposure to the underlying. Total return receivers lock in term financing rates and total return payers effectively sell an asset without ownership having changed hands. This makes them analogous to repurchase agreement and some banks characterize certain types of repos for example those on emerging market debt as credit-linked total return swaps. The main difference is that in a total return swap the underlying securities are not exchanged whereas in a repo transaction they are. This transfer of economic benefit without effecting a legal sale of the underlying asset can be advantageous for capital gains tax reasons. (See structured repo.)

Total return swaps are also used by banks to keep assets off their balance sheets. Instead of borrowing to fund the purchase of assets, a bank that wants exposure to a particular asset enters into a total return swap with a counterparty (sometimes called the warehouse or balance sheet provider) willing to buy the bonds. The balance sheet provider a bank or large corporate effectively funds the position of the investing bank which then pays the funding costs to them and receives a spread. If the originator of the transaction is itself balance sheet constrained, such as an investment bank, then it will buy the underlying bonds and then repo them out to the final balance sheet provider.

Example

An investor seeks exposure to a loan yielding libor + 350 basis points that a double-A rated bank has made to a Turkish corporation. The investor enters into a total return swap with the bank the total return payer under the terms of which it pays three-month Libor +100 basis points and receives Libor + 350 basis points plus or minus any change in the market price of the loan. If the loan’s market value remains unchanged over the life of the contract, then the investor earns 250 bp on the transaction. However the investor bears both the price risk and any early repayment risk on the loan over the life of the agreement.

Thomas A. Fetherston at the University of Albama put this together at some point in time – a mix of teaching notes, core concepts, a glossary and a 109 page handy desk reference that you would end up referring to if you work with derivatives in any shape and form.

I stumbled across this resource about 5 years ago and it had been stewing invisibly in one of the many resource folders I have on my hard drive. I believe it would be a crime to sit or hide on a resource like this. The Glossary is here and I will try and post the teaching notes over the next few days after turning them into bite sized pieces as and when I get time.

I looked for Tom’s home page but a Google search on Tom’s name only pulls up his authored books, no home page that I could possibly link to.