Raising funding for first time founders is a challenge. Already awkward conversations become more awkward due to misconceptions about capital, venture investors mindset, deal structure and incentives.

My credentials? I have never run a venture investing fund. I have raised capital four times. One exit, two holes in the ground. None of my investors made money. Two received partial returns. I ran through the start to fail/exit cycle for the first time in summer of 1992. In 27 years I have seen enough founders and investors shoot themselves in the foot without trying. In the hope of reducing deal fatalities, here are notes from conversations in Nepal last year about the fund raising process and investor mindset.

Decoding investor mindset.

With the arrival of Steve Blank and Alexander Osterwalder on technology startup scene our ability to understand motivation of customers grew manifold. As founders we learnt the process of decoding customer purchase behavior. We used business model canvas and value proposition frameworks to identify underlying customer pain and flow of actual transactions. I often wonder if we could do the same for venture investors we pitch to?

A large part of what follows is true for venture capital firms, but not necessarily true for Angel investors, individual investors or family offices.

A friendly neighborhood venture fund.

Some context and a few definitions.

A founder friendly venture fund run by two partners (fund managers) raises $15 million, makes 10 investments at the seed stage. After seven years the 10 investments return $51.75 million to the fund. The returns include one big hit (a 10x exit), two also ran (2x exits) , two partial return of capital (less then 35% of invested amount) and 5 holes in the ground (zero).

How much money did the two partners make out of that $51.75 million return? What about investors?

How would you grade this performance? Is this 1 hit out of 10? Or three? An an investor, would you grade the partners with an A or a C? How different is this model from other managed funds and trading desks? Are the odds better than winning in Vegas? How could you improve them?

The difference between a fund manager and a venture investor.

Or a GP and an LP.

The venture investor that you just pitched to is most likely a fund manager or a General Partner in an investment fund. What does that mean? A General Partner or GP runs the fund, makes calls to invest or pass, may sit on boards of firms that he invests in and is responsible for the performance of his investment portfolio.

A Limited Partner or LP invests in the fund being run by the GP and ultimately receives returns earned by the fund – which may be positive or negative. General Partner are commonly required to invest in the fund with the Limited Partners but the ratio maybe as low as 1% – 2% from GPs and and as high as 98% – 99% from LPs. Senior and experienced GPs may contribute more, younger partners are likely to contribute less.

The concept of carry and working for the Man.

While a GP may have some skin in the game (read: personal invested funds) his primary upside and compensation is linked to beating a benchmark rate of return that he and the fund investors have agreed on. Anything the fund earns beyond this rate is split on an agreed basis between Limited Partners and General Partners. This rate is called the hurdle rate. A common model is 2% / 20%. 2% of committed funds as management fee to cover fund expenses. 20% of returns earned over the hurdle rate distributed to General Partners. 80% returned to investors.

For instance, a $15 million dollars fund has a performance benchmark of $30 million. In seven years the fund returns $50 million inclusive of capital and returns. This means the fund invested $15 million and earned $50 million. 30 million of the 50 million, goes back to investors (LPs). Of the remaining 20 million, twenty percent, which is $4 million is paid to GPs. The remaining 16 million also goes back to the LPs. The managers earn 4 million. The investors put in 15 million and received 46 million back.

Beat the hurdle rate and you are golden. Miss it and you are toast.

The incentive for beating the benchmark for a fund manager is very clear. He can only truly eat when he performs. Without performance he can nibble (cover expenses) but won’t be served as full meal (earn a fair market wage).

In venture capital and investor speak we call this concept carry. A fund manager’s primary compensation for putting in the effort to run the fund, select investments that hit it out of the park and successfully execute exits, is in the carry.

If you are a founder, think about this for a second.

The venture partner or investor you are pitching to may have access to more deploy-able capital than anyone you know, but its not his money. It’s money that he is responsible for. Money that he has to return.

It is not enough from him to just earn a positive return. He must beat the benchmark. If he misses the benchmark, he is done. If he misses the positive return, he will lose his seat on the table.

The fund structure for new or fresh fund managers tends to favor compensating managers through carry rather than fund management fees. Which means they only get paid when the fund performs. If the fund doesn’t perform, they not only miss out on a large part of their planned compensation, they can’t raise a new fund. If they can’t raise a new fund, they can lock up their shop and go home.

But what about management fees?

While partners of the fund are waiting for fund managers to beat the benchmark, someone must pay expenses for the fund. These expenses are covered through a management fee that fund investors pay fund managers. The fee is not outrageous or obnoxious and in most instances is just enough to cover expenses. As per the 2/20 formula discussed above, 2% of committed fund size every year while the fund is investing. 20% of the return earned over the hurdle rate once the fund has liquidated all its investments and the books have closed.

A $15 million tech investment fund in our part of the world will have two General Partners or fund managers and a handful of Limited Partners. Each GP will bring one anchor investor who will write a big thick check and few small but qualified investors. GPs may also bring access to deal flow and domain expertise in addition to capital. This would be typical for a first fund. Most small funds in emerging and frontier markets are test runs for the GP and the market being invested. More money is available and is on tap if the fund and the GPs perform and market regulators turn out to be receptive and appreciative.

If not, for the LPs it is just discovery fees paid to explore and understand a specific market. It is intelligence they can use in later investments in other regions and with other GPs. LPs’ can afford to write off small bets and move on to the next more promising market or the next set of GPs that do deliver on what they promised. Once the LP’s decide to walk away from a market or a fund manager, they are not likely to come back. LP’s, like elephants, have long memories.

The only exception to this rule in our part of the world is Soft Bank Vision Fund where Masayoshi Son’s prior bets with Ali Baba, Supercell, FlipKart, Paytm and Yahoo!Japan earned him enough street cred to offset recent disasters. The Vision Fund has had terrible luck with some of their bets but terrific luck with investors. It’s not a great place for a GP but not a bad place either. They raised $100 billion to play with and are likely to get another $100 billion in the next 12 months.

Back to our lowly fund managers. From a fee structure point of view at 2% the $15 million fund receives $300,000 a year for seven years which is the time frame during which the fund will invest capital. This means our $15 million dollar will only have $12.9 million to invest, for seven years of $300,000 in fees adds to $2.1 million. This $2.1 million will be put aside as and when the fund makes a capital call to its investors and the money flows into fund accounts.

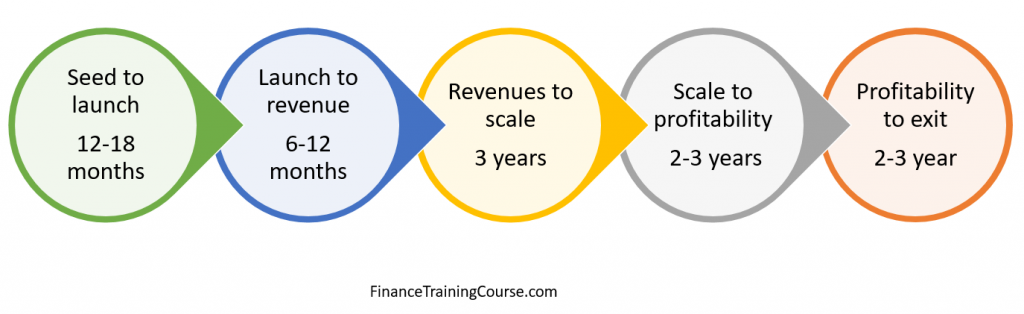

After seven-year period management fee may drop to 1% since sourcing deals and investing workload is mostly over and the fund managers focus is now to steer their charges towards reasonable exits. A typical fund may have an investment horizon of 9 – 12 years with the first 5-6 years used for investing fund commitments and the following 5 – 6 years for harvesting exits or liquidating disappointments.

If we assume another $400,000 in management fees for the last four years, net funds available for investments drops further to $12.5 million. This is terrible news for the fund manager because his investors expect him to make them whole – as in complete – as in return all the money they gave him – as in there is no net of fees returns in this community. He is already in the red for $2.5 million dollars before making his first investment.

The poor guy is not the Man or the devil in disguise. He only works for the Man. If his luck doesn’t hold, he won’t get paid for the work he did.

Why do you need so much?

Cut the fees you say. Why do you need $300,000 to run a four-man fund? While $300,000 a year may sound a lot to a cash starved founder, it is barely enough to cover all expense for the fund. Think about it for a second. What do we need to run a fund?

We need an office. We can skip it and run the whole from our study desk in the bedroom. Pitch meetings can happen at local coffee shops, on Skype or Zoom, on phone or in discrete hotel lobbies. Diligence can happen in startup offices or founder home offices or garages or our law firms conference room.

We need time to build a pipeline and source deals. We need to travel to check up on potential investments and startups. Once deals begin to flow, we need a basic filter to weed out pitches that don’t tie in with the funds’ investment thesis. We may need one analyst to build models, track progress, get data, run numbers, size markets, double check on month end reports, manage fund compliance and do the work no one else has time to do. We need to run due-diligence on short listed candidates, stay in touch and follow up with startups we have invested in. Raise follow on rounds with co-investors for the teams that hit their milestones and deserve allocation of additional capital. Pay the lawyers who vet the deals, manage investors who pay for the deals and coddle founders who think we have more money than is good for anyone, are on a power trip or are simply being tightfisted with capital that justly belongs to them.

There is that small bit about compliance within our fund registration domicile. Stuff that needs to be done every quarter to ensure the fund remains legit, is not raided by the FBI, the FSA or local regulators or have our GPs detained by Department of Homeland Security the next time they land in San Francisco or Chicago for their investor meeting. Compliance is not a nice to have. If you want to keep on flying around the world raising and deploying capital, you can no longer afford to get it wrong.

Compliance is not just paperwork but also fees that need to be paid to the auditors, accountants, lawyers (again) custodians and trustees of the fund. By the time everything is taken care of and paid for, we are hardly left with US$50,000 per General Partner.

Well its more money than I have made working as a founder most years. It doesn’t sound like a lot till we find out that our poor GP left a cushy $500,000 job in New York or Chicago or Frankfurt to come run this fund, has 2.5 children, needs to cover their school fees and his mortgage and has already invested his total available liquid net worth in the fund to convince his Limited Partners that he absolutely believes in this market and this batch of rag tag, no way they are going to make it or win, founders.

If he makes it, and not a lot of them do, he can laugh all the way to the bank. Sometimes, not always.

If he doesn’t, he is out of work. Period. LP’s talk to each other and are not a forgiving lot.

Those are the lucky ones.

The unlucky ones are still stuck in the graveyard of living dead ventures trying their best to liquidate their holdings so that they can return something to their investors and close their funds. These poor souls can’t go home or move on till the evil deed is done.

Founders walk away in a huff all the time. GPs unfortunately sign the till death do us part contract with LPs. Even if they write off the full investment, they are the ones who get to turn off the lights before they leave. The living dead accumulate liability like unwashed dishes in a bachelor pad kitchen sink. Long after the original founders are gone, it is the GPs job to clean up the sink, fumigate the apartment and terminate the lease. You can’t close the books on a fund that still has open, festering wounds.

All this before investors who want to cut and run (want their money back) every time someone explodes a firecracker in our backyard, markets take a dive, or their liquidity gets wiped out by a correction in the asset class they thought was safe.

If you still haven’t got the memo, here is what I am really trying to say.

GPs’ need the carry to continue to earn a living. It’s not just compensation, carry is a license to raise your second, third and fourth fund till you hit an Ali Baba or Supercell. If you don’t, you continue to work for the Man.

As someone who has done that for many years, let me tell you, it is no fun at all. You think it is a dog eat dog world as a startup founder. Try and run a venture fund for a change. I wouldn’t work for these conditions. To my friends who still do, you guys need to get your heads examined. There are cheaper ways to lose your hairline and your sense of humor.

Lets talk about the math.

Back to our GP at the $15 million tech fund.

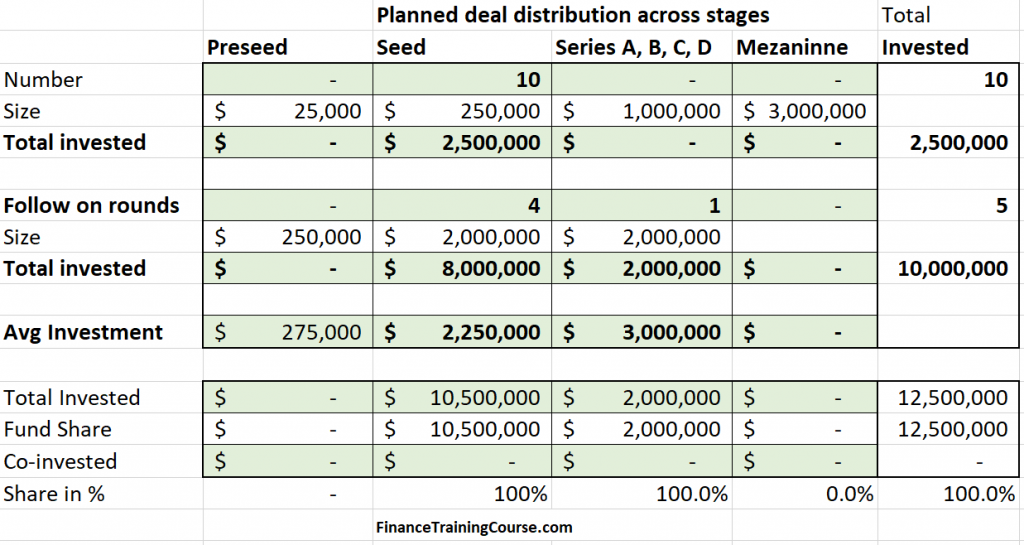

The available fund size is $12.5 million. Remember we put aside $2.5 million in fund management fees to cover expenses.

Most GP’s will slice available funds in multiple layers.

The first layer is two to two and a half million dollars allocated to seed capital. Typical bite size – $250,000. Roughly ten planned investments or candidates.

The ten investments are the reason why we need two GPs. Typical GP can effectively run five seed transactions in parallel. There are exceptions but for now we will stay with normal people.

Remember as venture investors these are guys who are going to add value, not just write checks. Which means they will be involved in major strategic decisions and roadmaps. They want to open doors, help with recruiting talent, lay the groundwork for series A, B and C, look for partners and acquisition targets, be an effective sounding board, help with setting the right vision and direction.

They also must run the fund on the side. Five transactions per GP it is. With a bigger fund, you would either increase your bite size or add more partners.

GP Challenges.

Which brings us to our three big challenges for a GP.

Challenge number one. The life of a typical fund runs 7 to 12 years. A seed investments takes 6 to 10 years to get to an exit. For a decade a GP stays involved with the founders and the team. He is essentially married to the idea. He wins if the team wins big. And he will stay with the team as long as he believes in them. But if the team misses all the shots it takes or refuses to listen to good advice or stays in denial, or suffers from a terminal self inflicted wounds, what should the GP do? What would you do?

Remember you have 4 other charges that you are responsible for. If you have a non-performing, tantrum throwing, self entitled attention seeker in your class who is distracting you from helping four other students with their goals, what would you recommend? As a track coach, I throw non-serious kids who continue to distract the team, off the team all the time. A GP would do the same.

Challenge number two. Would you spend ten years working with a team on a concept that you didn’t care about? That you didn’t think worthy of being done? Or a team you didn’t like? Or a founder who couldn’t stand for more than ten minutes? Would you get married to them for ten years?

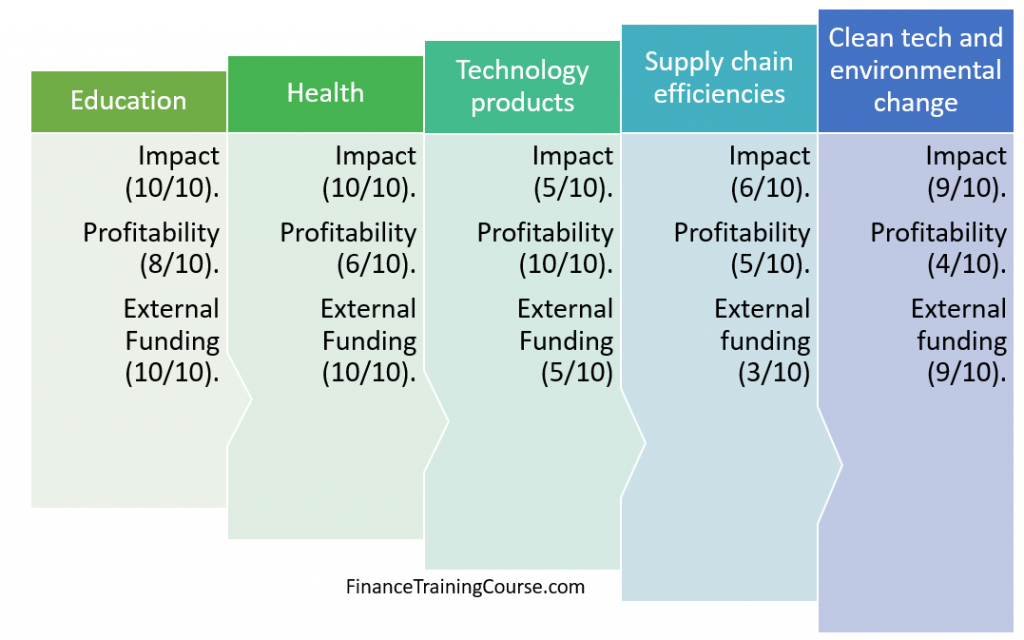

I know we have spoken a great deal about numbers and returns and carry and fees, but that is not the real game. The real game for a GP is to get involved with domains they really want to change, problems they really want to solve.

Great GP’s raise thematic funds that focus on themes and thesis that they really care about. They specialize in sectors and segments they understand and can influence because of their history or their street cred. They want to work with founders who want to solve the same problems, who understand that they can’t do this alone, that they need help. For them it’s not about running a fund that returns 10x invested capital. Capital is just a tool. Returns are just a number. The real benchmark is the legacy you leave behind.

It is changing behavior, landscapes, outlook, motivation, trends and patterns that really drives GPs. Returns are just a filter. Great venture investors also bring deep expertise and exposure to relevant domain to the table for the same reason. When you add them to your team, they turn the odds in your favor. They open doors, share perspective you weren’t aware of, allow you to focus on your execution and scale game while they take care of bigger irritants.

Challenge number three. This is the most painful one for founders. There has to be a clear path to an exit. It has to be within the life of the fund. Depending on when the investment is made you are looking at 7 to 10 years to sell and walk away from something you built.

You have to buy into the exit as a founder. If you plan to keep on growing your business to infinity without an exit, with venture capital, you are in for a surprise. The fund has a finite life, investors have to be paid back, the exit is already baked into the script. Not doing the exit is not an option. And no, share buy backs don’t return the fund and don’t count as a hit.

Making money? Returning 10x?

The seed round is attractive because of lower valuations (read: higher returns) but it also takes the longest to pay back and exit. Transactions that return 10x to 30x often enter the fund at the seed round. When you are looking for higher returns in emerging markets, a seed fund makes the post sense for venture investors.

For our tech fund that made the ten seed round investments, here is how it is likely to play out over the next ten to twelve years. There are many variations of what follows, but they all ultimately end up with similar math.

Of the ten investments four will graduate to series A. Two will fold (fail) with some money coming back to the fund. Four will only leave a hole in the ground. That is all ten accounted for from the first round. All of this will happen within the first 12 months.

The second and third layer of the fund will allocate a million dollar each for series A and B for the four winners from the seed round. That is two million per winner, eight million in total across two rounds of investment. The two rounds will run the course over three to four years.

By this point we have allocated $10.5 million of the $12.3 million in available capital and we have just crossed year five.

One of the four from the seed round will go on to series C and be the big winner and return the fund (we hope). It will also claim any available, remaining left over capital for series C. Let’s also assume that because we had a kick ass GP, all this was done and wrapped up by year 7 for our big winner.

One of the remaining four will fail post series B and will be written off completely – another hole in the ground. Two will not be anything to write home about but will have exits that will make the news, create good will for the partners and return double the invested capital. Not a great compounded annual rate of return but money that is back in the bank.

This performance or track record would be considered great performance anywhere in the world. A hit rate of 30%. 3 winners out of 10. You couldn’t have asked for better results.

How would the math work in terms of generated returns with the above performance.

Lets take a look:

Capital raised = $ 15 million

Capital deployed – $12.3 million

One – return the fund, 10x return transaction

- Amount invested = 2.25 + 1.8 = 4.05 million dollars.

- Amount returned = 41 million dollars

Two – return 2x capital transactions

- Amount invested = 2.25 x 2 = 4.5 million dollars

- Amount returned = 9 million dollars.

Five – holes in the ground

- Amount invested = 4 x 250,000 + 1 * 2.25 million = 3.25 million dollars

- Amount returned = 0

Two – partial liquidations

- Amount invested = 2 x 250,000 = 500,000

- Amount returned = 175,000

Total return to fund = $50.175 million

Venture investors vs GP? Who made what?

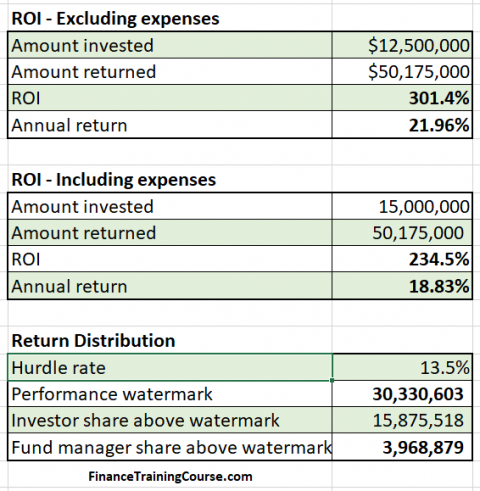

Good questions, let’s take a look at the results from a distributions perspective. Table below has three sections.

The first calculates annualized returns net of fund expenses. The second calculates them inclusive of expenses. In simpler terms this means that in table one the deployed capital is $12.5 million, where as in table 2 its $15 million.

The third and final table shows the returns distribution between the GP and the LP.

Because the hurdle rate was set 13.5%, the performance benchmark the GP had to beat was 30.33 million. $30.33 million is what $15 million would grow at a compounded return of 13.5% a year. Depending on how you defined it, the annualized rate of return earned by the fund managers ranged from 18.9% to 21.9% per annum for the 7 years the fund existed.

The GP’s beat it by just under twenty million by earning 50.175 million in returns to the fund.

20% of this twenty million has been earned as carry by the GPs. The remaining 80% will go back to the LPs. Because there are two GP’s they will split the 4 million between themselves.

Two million dollars for 7 years of work in which you gained 200 kilos, your hair turned white and your kids grew up in your absence. Also you are no longer on speaking terms with three of the five teams that left holes in the ground. But you returned 2x to investors and you won’t have any trouble raising a 2nd or 3rd fund with that track record. On this fund as a GP you made just under $300,000 a year for 7 years. If you add the $50,000 a year you drew as salary during the 7 years, you can bump it up to $350,000 a year. Personally you are still in the red for $150,000 when compared to your cushy New York Job. Excluding bonuses.

But the amount you made on your first fund is not important. With this track record you can raise a second fund which is 3 times larger. With the same track record will allow you to earn $600,000 a year as the senior founding partner of the firm in another 7 years.

I don’t think its fair compensation but that is all she wrote. That’s just me. Remember, now that you know, be kind to your GPs.

Additional readings and references

- The Founders guide to understanding investors, Anuj Abrol, Hackers Noon, https://hackernoon.com/the-founders-guide-to-understanding-investors-4f99eafe2273

- Resources for those interested in venture capital and private equity, Jason Heltzer, Venture Evolved, https://medium.com/venture-evolved/resources-for-those-interested-in-venture-capital-and-private-equity-3964d0734273

- Super Notes on super founders, Elie Steinbock, Hacker Noon, https://hackernoon.com/notes-on-super-founders-11254f693267