I teach a course on building startups to undergraduate students at a local university. The audience includes sophomores, juniors and graduating seniors. We cover themes that touch the startup mindset, road maps to credibility and launch, customer personas, pitching, selling, product development, innovation and founder profiles. As with all courses I teach, the emphasis is more on learning by doing and less on long extended lectures, monologues or speaker sessions. We do get speakers but they come to mentor and judge teams and answer questions related to their area of expertise. Over four months each team picks up an idea and try and seek responses to basic questions that assess if their project is worthy of future consideration. If the startup idea meets all their filters, they go ahead and craft a pitch that they can use to introduce their big idea to the world. There is no requirement for the idea to be a for profit venture. We are equally interested in not for profit concepts that can create social impact.

This weekend after a typically grueling submission a student finally asked me, what is the point of this course? It wasn’t a rhetorical question. I could see the frustration spilling over in her eyes. Why do you teach it the way you teach it? Why do we have to do all this work? I am lost and there is really no end in sight? Why can’t we just take an exam and be done with it?

Academic courses tend to be structured. There is a curriculum that is taught and presented. There is a grading outline that you are graded on. Typical models include attending class room sessions, memorizing or working with frameworks and then being tested on them in same form and you are done.

Teaching someone to build a startup from scratch on the other hand is a study in chaos. The one thing that is missing is structure. There is a framework but its application is not paper based or linear. Its linked to real life. And in real life things tend to break or go off on a tangent. Which is the reason why the course is so painful to work with. In most instances when you hand in your literature or partial differential equation assignment after diligently following the guidelines shared by your professor for the entire week, there is very little chance that they will say this sucks. Prose is prose, equations are equations, frameworks are frameworks but the only certainly in working with startups is that version one of whatever you produce will most definitely suck. Experienced warriors who have spent years in startup trenches call it learning to live with iterative marginal improvements.

I thought it was time that I wrote something that explained the mindset behind the course and the core themes that should stand out amidst its chaos.

Building startups. Origins and evolution

Here is some context.

Over 15 years with changing market dynamics and student profiles, the course has also evolved. In its first version our focus was showcasing the many reasons new ventures fail. Because we felt that as a community and society we didn’t look at failure with the right perspective. We thought it was important students understood that failure was part of the equation; something they had to learn to live with if wanted to walk the road that led to founder land. The realization to the quote the epitomized the central theme of the course in early years – Writers write, painters paint, founders fail.

The next edition made students create and submit a power point pitch to be graded by external judges. The thought behind the redesign was that while we could come up with as many interesting ideas we want, learning how to pitch them in a short 5 minute window required a great deal of work. The pitch had to walk away from the typical engineering challenge – look what a cool thing we built. The lens was pointed squarely on customers and understanding their pain points. Rather than focus on technical and design challenges these pitches were driven by customer use cases.

In the third iteration the power point presentation became a YouTube screen cast. The last three hour class for the course just wasn’t enough to accommodate all 20 pitches. We spent a few versions of the course staying back in campus all the way past midnight just so that all potential founders could pitch their heart out in real time.

The YouTube screencast gave the students a chance to rehearse and tweak their pitches before they came in front of the world. It gave the judges an opportunity to get a chance to filter their favorite teams ahead of the formal screening. It gave all of us something to look back too in later years.

The final version, the frustrating one we are teaching this year, the one that forty bright students find difficult to digest and awkward to work with is the one in which the final pitch needs to go up on either YouTube or Facebook and must score a certain number of views in less than one week. Last year the threshold of views was 10,000. This year it’s jumped to 50,000 views.

Simple power point pitch are out. The 90 second clip can play on customer use cases, audience focused messages or an emotional call to action. A promotional video that gets prospective customers, partners, employees and investors interested enough in the underlying idea.

So back to the big question. Why? Why this format? Why this specific course plan?

Building startups. The five themes

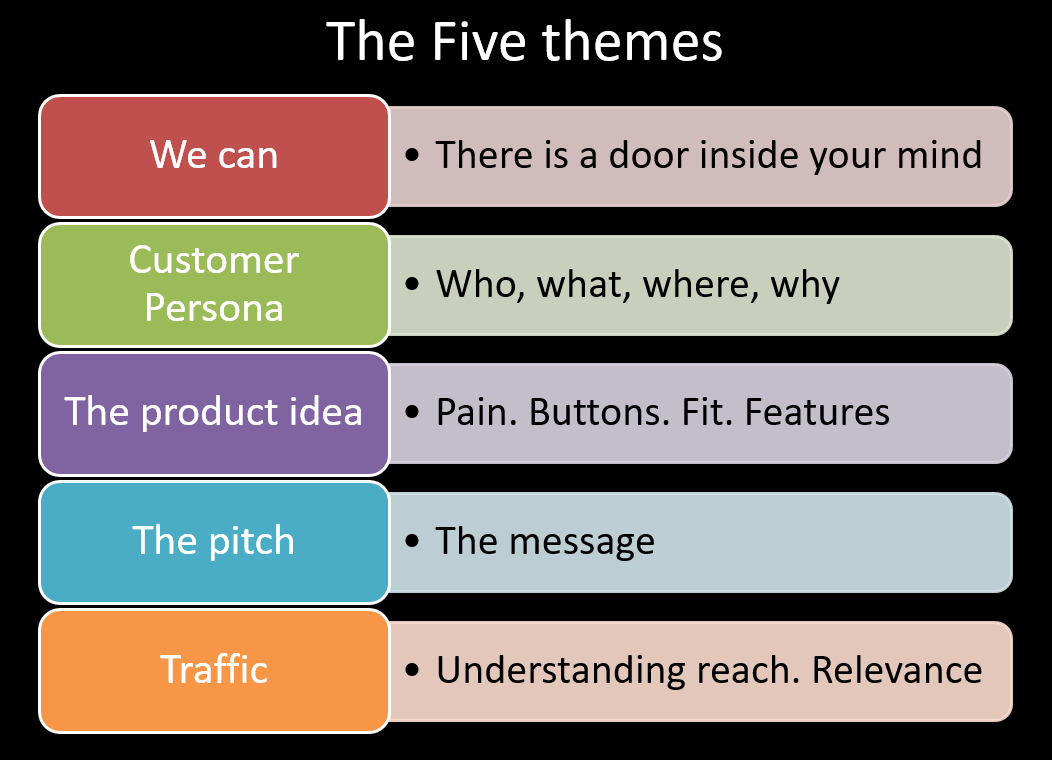

There are five core themes in the course. Five paths that teams need to master.

Building Startups. The mindset.

Working with constraints. Winning within the local market. We can.

How do you convince a group of 21-23 years old that they can change the world? The first thing we have to convince them of is that they can. They have the magic ingredients, the only thing missing is the awareness that they can. The challenge is that our social signaling mechanism is setup to program the exact opposite message. Don’t be the odd one out, don’t take risks, be safe, don’t fail, don’t stand out, there is safety in numbers. Avoid complexity, ambiguity and bets with potentially large payoffs. Follow the herd, please do whatever you have to do but just don’t fail.

The theme in the first four weeks is focused on you can. Maybe you should. The course doesn’t resonate with every student but we try and hit as many buttons as we can – innovation, failure, going against the odds and taking the road less traveled by. The stories and role models are all local so that the class can relate. The settings are local so they know that this has been, this can be done. This conditioning is necessary so that when we come to the crunch month at the end of the course we can come back to the message again. But side by side with this conditioning we also emphasize that it will take a few cycles to get things going and working. That there will be a great deal of disappointment and many false starts before you get your act together.

The key to breaking performance barriers is simple. There is a door inside your mind. You need to open it and walk through it. That is all you have to do to break free of the walls you have built around yourself.

Building startups. The customer.

The persona. Understanding who holds the keys to the kingdom

Making things is easy. Selling them is difficult. The first step in the sales process is understanding who the customer is and what does he or she needs. Engineers, not just students, tend to build first and think about selling later. Customer, pain, product that is the order that works. Not product, customer, pain.

Selling that works, that delivers results year after year is based on a deep understanding of what drives customer to purchase products like ours. Rather than focusing on selling, it focuses on solving problems and building relationships. The lens switches to customer pain points and how our product attributes need to address those points. Two exercises are run again and again – building customer personas and linking those personas to specific customer pain points and product attributes. So that when we design our messaging it is in alignment with the customer perspective, not ours.

Once again we focus on reworking the sequence. Start thinking about the customer as soon as you start thinking about the product. Sometimes even earlier.

Building startups. The product idea.

Matching it to the customer’s pain. Learning to design products based on customer needs.

How do you prioritize product features based on customer preferences, resource constraints and delivery potential? What should drive your MVP feature set? Product differentiation, competitiveness or customer appeal? These are the questions that we try and answer as part of the customer market product fit exercise run as part of the third theme of the course.

The customer product market fit exercise is currently the weakest part of this course. Since the focus is on getting students comfortable with the conceptions of idea generation, customer personas, pitching and attracting eyeballs and not core product development we only do two sessions focused on customer product market fit. The expectation is that in depth product development is covered as a separate standalone course in the curriculum.

Building startups. The pitch.

What makes a pitch? Putting it all together.

At a class reunion or a social mixer a random stranger asks you, “So what do you do?” At an investor round table, a prospective investor follow through with another question, “So how is it different about what you are doing when compared to x” You grandmother wonders out aloud about what you have been doing after college and is that really a good usage of your education? How do you respond to all of these questions?

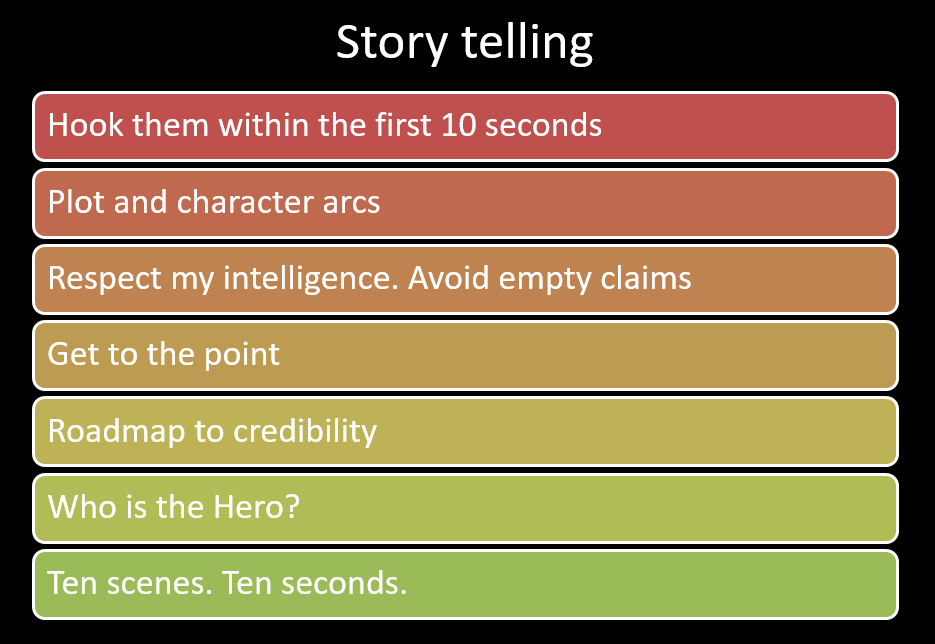

A pitch can be described many ways but the simplest is a collection of to the point responses to common queries. There are short 30 second versions and long 30 minute versions. A formal pitch will include the reason for being for your business, the problem being solved, customer personas and validation of customer pains points, product market fit, roadmaps to credibility and sometimes even the business model canvass.

Within the time allotted for these sessions we do all of that but rather than presenting a formal pitch our focus is to get the story and the story board right. The consistent message that you want to communicate to the world as you present your concept for the very first time. The consistency is important and indicative of your maturity as a founder.

Building startups. Understanding Traffic in the real world.

You have spent the last four months working on your self-image as a founder. You now know that you can. You have built and validated multiple customer persona and have a brilliant pitch and launch video ready.

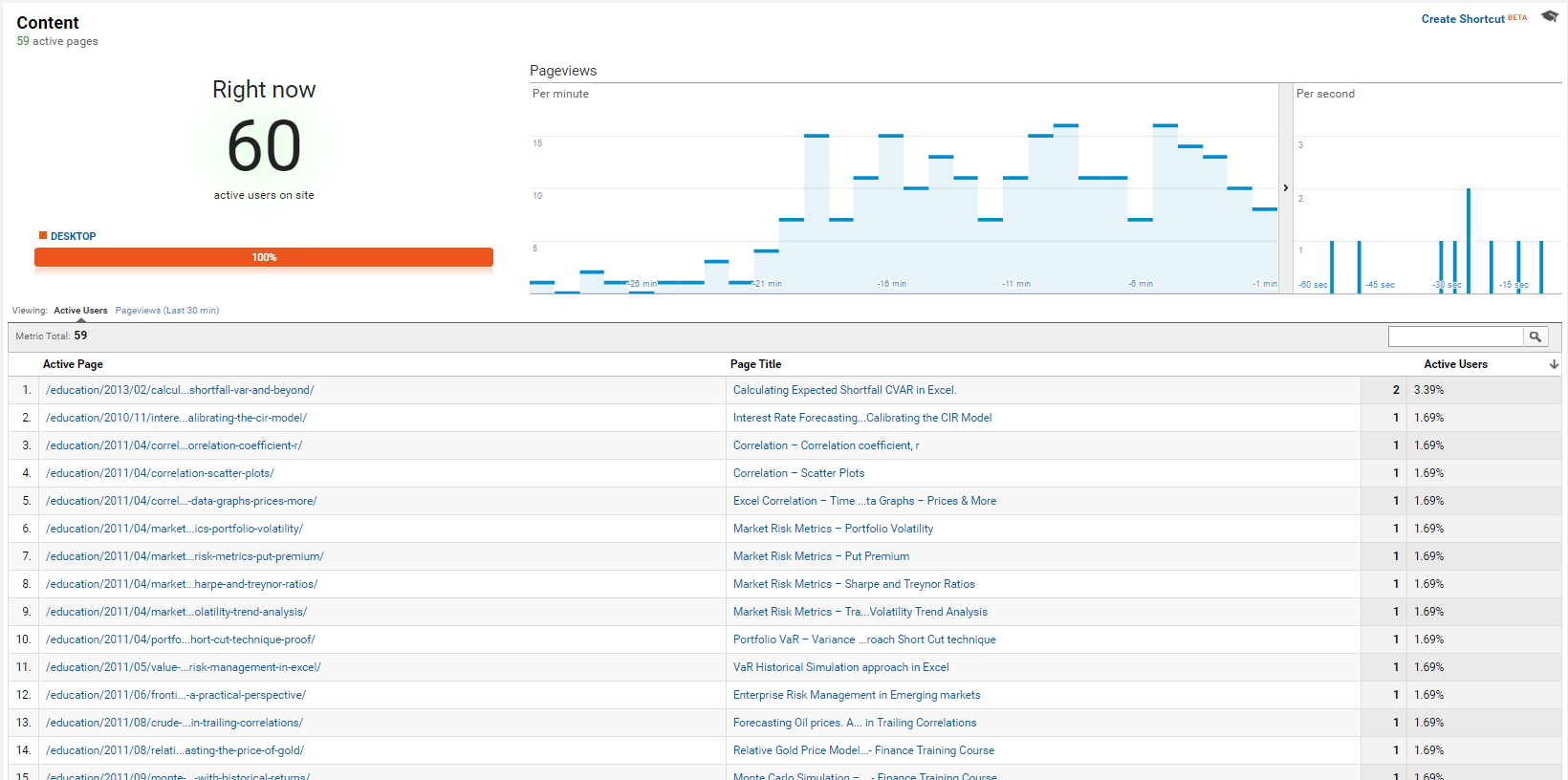

You post it on your YouTube channel and your Facebook profile with great fanfare on Monday morning. By Friday evening, five days later, you have clocked all of 237 views on Facebook. The YouTube tally is even more depressing. A total of 69 views, half of them friends and family. The power call to action you took a full month to craft resulted in 50 clicks to your state of the art landing page. It’s anticlimactic enough for you to go home, hide in a corner, shed a few tears and never come back to startup land again.

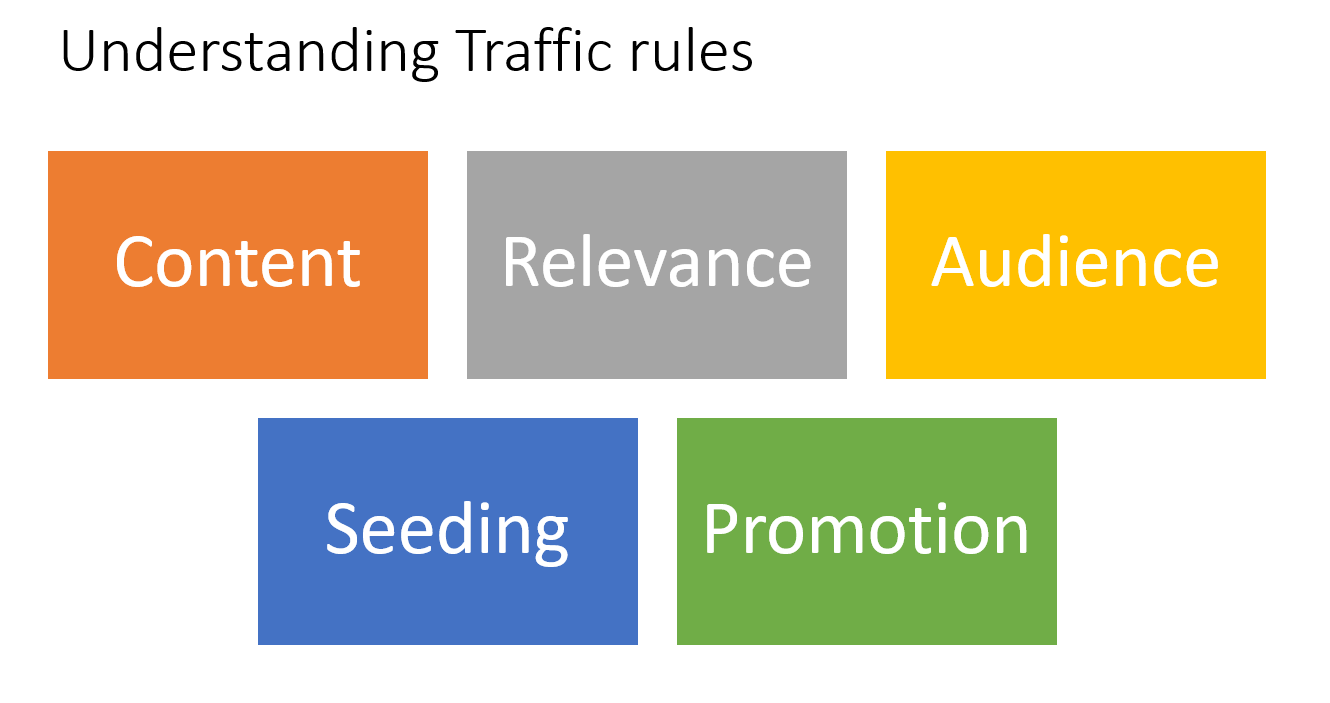

While the first four themes focus on the craft of validating and pitching, the final theme is dedicated to understanding the traffic game. How do you get eyeballs to your message? What does it really take to generate those huge views YouTube channels and Facebook pages dream about? What really defines and drives virality?

Understanding this is key. How do you produce messages with impact that drive traffic your way, day after day, year after year. That make it possible for you to make an instant connection with your audiences in less than 90 seconds.

Building startups. Putting it all together.

To succeed as a founder you have to learn to get all five themes right. Yes we all struggle with limited time, competing priorities, resource crunch and bandwidth challenges. The ones you make it figure out how to balance all five balls. The ones who don’t drop a few. Teaching technology entrepreneurship is very similar to teaching swimming. It doesn’t matter how good a teacher you are, if you can’t get the kids in the pool, they will never really learn to swim.