“In that direction”, the Cat said, waving its right paw round, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad.”

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.” — Chapter 6, Alice in Wonderland

A follow on post to our medium article – Cloths of heaven – a parting note for my CS and EE students from last month. This week I do the same for my treasury and finance students across the world. There is a method to my madness. Its called experiential learning. If you ever wondered about my sanity, here is a chance to hear my side of the story.

When I first started teaching in September 1995 I just wanted my students to hit the ground running. I wanted them to reach employment markets without skill gaps that employer (like my firm) found awkward and annoying.

I had been hiring graduates from a top computer science school and found a few core skills missing. The kids where sharp, hardworking and dedicated. They had done the course work, read the text books, completed their assignments but had missed the defining lessons from their curriculum. They came into the workforce thinking they were ready to do anything. Their employers found them lacking. It was my job as an instructor to fix that. That mindset has stayed and served my students well over the last two decades.

Over the years I have learnt that there is a term for this mindset. It is a variation of hands on experiential learning – rather than learn by rote you learn by doing or experiencing. Great teachers have been doing this well for generations including many who taught us, the current set of old fogies, as students.

If the approach is so good, why is it rare? One reason: experiential learning is significantly more difficult to design, execute and deliver than conventional forms of learning. As an instructor it requires a complete reboot. We no longer look at our audience as students. We look at them as partners. As a student the effort required to do well in such a course also goes up by orders of magnitude. It is no longer enough to just do the end of chapter questions. You have to internalize lessons, extrapolate and apply them on applications you are not comfortable with. You are no longer treated as a student; you are a practitioner.

The bottom line – more work, hard work for all parties involved. You can’t attack such a course with linear thinking, either as an instructor or a student. You can’t slack off, you can’t hide in a corner, you can’t ride the coat tails of your group partners. The payoff is in the impact it creates. Supposedly.

Supposedly because without you, the students, participating as willing subjects, there is no joy.

For instance, let’s take a look at the portfolio management and optimization course I teach to executive MBA students and bankers. A typical business school course on portfolio management begins with CAPM and APT, throws in a handful of cases, spends a little time on extending the original model to multiple asset classes, briefly addresses risk metrics and closes with an allocation based exam or project. This is not a bad design and a qualified professor can do well with it. How do we know? That is how we were taught portfolio management thirty years ago. The best book on the subject in the ’80 and ‘90s followed the same structure.

But it is a design that treats students like students. Not portfolio managers or as professionals responsible for making allocation decisions on a filtered security universe. It lays the foundation for theoretical excellence but doesn’t do enough on the practical application front. How do you translate that framework to an Excel Sheet / Model that works across 50 securities rather than 5? How do you know whatever you have built is effective and accurate?

As an instructor how could you change that? Here is what we did.

When we first started teaching the Portfolio Optimization course, we went looking for our old text book. When we finally found it, we put it down in a hurry. It was still the best text book on the subject, but it wasn’t relevant for our audience. Evening executive MBA students in the class room for 18 hours across six evenings. What could we teach them in six days that would stick for the rest of their lives?

We taught them to work with their hands using the problem statement below:

You have just quit your cushy job with Goldman Sachs Asset Management (GSAM). You have hung out your shingle outside the door of your office and raised a bit of money from loyal clients. Now it is time to earn your keep and fees. If you are a one-man allocation team where do you start?

You start with data and an allocation thesis. Good data drives decisions. Do you know where to find it?

So begin by creating a real world dataset of technology stocks, currencies, commodities and bonds. Apply increasingly complex optimization frameworks on that dataset and record performance and results. Look at year on year trends. You don’t have access to your old employer’s super computers or the army of quantitative programmers well versed in R, so build the model in Excel. Compare the performance of each investment framework (strategy) with its peers and pick the one with the best results. Done? No.

Now that you have a candidate for an allocation model, back test and evaluate it. Test it on a year on year basis and on the last two down market cycles. How does the model hold? If it doesn’t what would you tweak to make it work? Make the tweak and run the cycle again. By the way which metric did you use to evaluate portfolio performance? Does it map directly to your clients’ incentive model?

Remember its real client money you are dealing with and if you blow the benchmark, back to your boring Goldman job you go.

Real world models need to be customized before they can work with real world data. Our common challenges include absence of active secondary markets, price continuity on a daily basis, evolving regulatory frameworks and a general distrust of models, process and analytics when it comes to markets. Markets also evolve and mutate behavior over time making it difficult to find stable models that maintain their fit over time. Sometime building models is the easiest part of an engagement, convincing stakeholders to use them is a much bigger challenge.

This is a lot of work for 3 credit course in a business school. It is a lot of work for students and faculty teaching the course. If the class and the instructor are not sufficiently motivated, you can’t teach a course this way. To do this well and in the time allotted you have to show the students how to do it, piecemeal and then ask them to try it themselves. You can throw them in the deep end of the pool only if you are willing to stand by with a life line. A lot of instructors make this mistake. They ask students to do the impossible but then don’t up their game enough or budget time for guidance and mentoring. Partners, not students, remember.

Most academic business school courses would start with two hypothetical stocks. They spend time on deriving the basis for CAPM and APT and the challenges with extending them in the real world. Cases they discuss will cover core topics and allocation choices at a high level. Some may even require you to build an allocation model with a dozen odd securities.

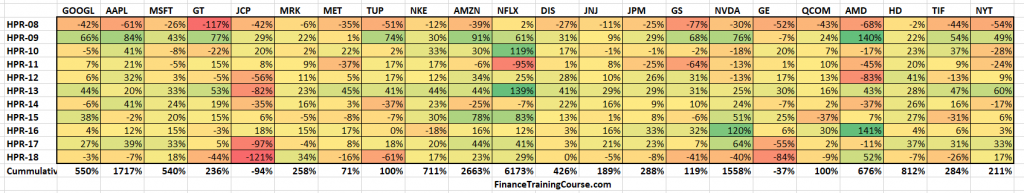

How did we compare? Our securities universe had 40+ real world investment choices with a decade worth of data starting from August 2008, the start of the last major financial crisis. A decent academic program would quote half the number of tickers and two to three years of data. Even if they could provide a similar data set, the question you ask set the tone for the experience. Real world questions, not end of chapter assignments.

What is the difference? The difference between being good enough to carry a conversation in an interview but not sufficient to jump across the table to the side of practitioners. Don’t be good; be better.

Going in we knew as instructors which strategy would dominate this specific data set and what would be the big lessons students would find. But letting students discover the answer by actually doing the work is so much more powerful than just telling them. “With hindsight beginning of 2017 was a great year to invest in Google and Amazon but a terrible year to buy JC Penny” This is a statement that tells and will soon be forgotten.

Understanding what made 2017 a good year and how to identify similar good years in the future before they become good years would be the real take away from the course. By making sure that students do bulk of the work themselves, that they explore lessons on their own, that they discover insights by opening doors and posing questions, learning can turn into a powerful and moving experience.

I follow the same approach with treasury management (price a treasury product term sheet and sell it to a client – (hello IBA evening)), entrepreneurship (pitch an idea by building a 90 second video aimed at your ideal customer. Go forth in real world and push traffic to it), risk management (how bad things could really get by trading against the real world), financial modeling (how much does your product cost to build and sell?) and leadership under crisis (how do leaders behave in crisis and how does that define them and us?).

We get the same reaction every single time. You can change the city, the country, the time zone, the subject, the degree as well as the academic institution, students initially react exactly the same way.

Why does he do the things he does? Where is the method in his madness? Is he out of his mind? Why are his expectations so unrealistic? What does he want from us?

Why? Because it’s a lot of work for a single term course. Especially, if you approach it like a student. But if you flip your mindset and start thinking like a professional, it’s a great opportunity to improve your game.

The experiential learning method only works if project or assignment output comes as close as possible to real work assignments. Comparable to what we are expected to submit in professional life. If grading and assignment complexity reflect what employers expect to see at work, students step into real world roles with ease.

A good measure of work product quality is the ability of the student to build up on it. So often courses we teach take a building block approach. Phase I fits into phase II, phase II leads into phase III. If your work product wasn’t strong enough you often have to redo everything by the time you get to phase III. It increases the effort put into the course but it also reinforces the concept that superficial work will ultimately come back to haunt you; so it is best to do things well and do them right once, rather than doing them again and again.

We are often asked by students about why our courses are so painful? This question goes to the heart of our teaching philosophy. Why do we teach? We teach because we were blessed by teachers who showed us what was possible when we were willing to go beyond the limits we had defined for ourselves. Redefining personal limits requires you to step outside of your comfort zone. Unless you are used to doing that on a daily basis, ditching comfort zones for the unknown is always a painful experience.

Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where — ” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“ — so long as I get somewhere,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.” — Chapter 6, Alice in Wonderland.