Seven finance lessons for founders is inspired by a lecture I deliver for computer science and electrical engineering students at Habib University. A slightly different version of this lecture was also shared with technology founders and startups at national incubation centers.

Why finance?

As engineers we are under exposed to concepts from the world of finance. My introduction to finance occurred when I started building backend accounting systems. While I studied computational finance, the finance of real-world decisions is different. We cover it in textbooks but real life throws curve balls that are beyond the scope of our curriculum.

You do not need to have an interest in finance to understand these concepts. Personally, as a founder, not being aware of these lessons caused me a world of trouble. I hope you can learn from my mistakes.

If you would rather hear me speak than read, here is the play list of my lectures from Habib University for the MGMT-301 course for founders.

If you would prefer to read, read on.

Lesson one. Opportunity cost.

When you wake up on a weekend morning, what do you do first?

Do you reach for your phone to check your email or social apps, or do you rush to get ready for a pre sunrise morning run by the creek? Can you do both?

To make it to a pre sunrise morning run I have a short window to rise, hydrate myself, put my kit on, get in the car and leave for the run. If I miss that slot, I will have to wait till the next day for the sunrise slot.

How do you decide which one to choose? Opportunity cost is all about choices. Choices that allow you to pick one path over the other. Like choosing to run by the creek or by the sea. You can do one, but you cannot do both at the same time.

Evaluating tradeoffs and choices is the essence of opportunity cost.

Sure, somedays you will skip the run. Somedays you will check and respond to emails first. Somedays you might even get to do both but not at once. You can run first and then check email, in that order.

I can never check email and respond and then go for my sunrise run because whenever I do, I run late. Too late to witness the horizon break into shades of ochre and the sun beginning to peek from where the creek meets the sky. Blink and you will miss it.

It is a run, but not a sunrise run.

A sunrise run is a magical twenty-minute window of peace filled with light, colors, and sea breeze. You can catch it once a day but only if you start early. Email you can check anytime.

Beyond email and sunrise runs, the other difficult choice I get to speak on is the choice between products and services for technology founders.

Should you build a product company or a services company? Can you do both?

A product company has a steep learning curve because it requires a different skill set than a services shop. The skill set is a mix of talent, experience, and exposure to the product world.

There is also a sharp cost curve as we run through the product market fit loop which is iterative. It takes 6 – 8 tries to get our recipe right. We are wrong more often than right in our early years in the discovery cycle. It helps if the team is comfortable with failing fast and failing quickly so that they shorten the path to the right mix.

Someone must pay for the 5-6 times we are wrong. Most founders cannot afford to finance that phase organically, much less run through the development maze every few years. Hence the common path to products through services.

Services offer an interesting compromise. You can build capacity, reserves and experience while being paid by others and then when the time is right switch to products. But is that really the case? Not everyone is lucky. See products versus services.

When you feel something needs to be done and you need to make a choice that requires you to pick one path over another, step back. Take off the emotional cap. Evaluate tradeoffs and then decide. Choices have consequences. Some paths converge, most don’t. There is a chance you won’t come across the same cross roads again.

Lesson two. Sunk costs

Can you fix bad code? Code so bad that it will make you cry. if you see code that damaged or broken should you fix it? Or should you bin it and rewrite it all over again?

That at heart is the debate around sunk costs. The effort or capital you have put in building something should no longer be a factor in your decision to spend more time or allocate more capital. Just because you have worked on something for four years you should not factor that time in your decision before you give up and walk away?

Some businesses are like bad code. Better to bin them and walk away then attempt to fix them.

When the time comes to do that, should you look backwards or forwards?

The correct answer is forwards. What you have already spent or invested in not coming back. It is in the past. A decision that cannot be reversed.

But you can still control what you will spend in future. Evaluate the decision to invest or spend more irrespective of what you have put in. We often think that allocating more capital may allow us to recoup our original investment. While that may be true occasionally, capital is not going to fix a business with bad DNA.

The key driver is not history. It is the allocation of capital and effort in future. Remember opportunity costs and tradeoffs. If there are better investments and returns available do not make a sub optimal decision.

While we may think we understand opportunity cost and sunk costs, we are often married to the past. Rational perspective can get clouded by emotional attachment to teams or businesses.

Lesson Three. Building Models

I have been building models for three decades. Model building, computer science and computational finance have many common challenges.

- We are so focused on building we often ignore the reason why we are building in the first place.

- We pick up a model and apply it. Models need to be tweaked. They need to be set right and calibrated to the correct context.

- Most models are only valid for looking backwards. They do a great job of fitting data to history but fail when the same relationships are extrapolated to future.

- Models are based on incomplete and imperfect model points that link them to real world. Underlying equations suffer from known errors but are still useful in the absence of other choices.

- Models break more often than they work.

- All models are wrong, but some models are more useful than others.

How do you apply modelling to startup revenues and markets? If the ethos of modeling is driven by the fact that all models are wrong, how do you effectively model revenues and markets? More importantly how do you use such models? Should you invest in building models or not?

If you try and model revenues in markets to which you do not have exposure, where you are missing context, your models would not just be wrong. They will be off by orders of magnitude.

The key is context. How important is context?

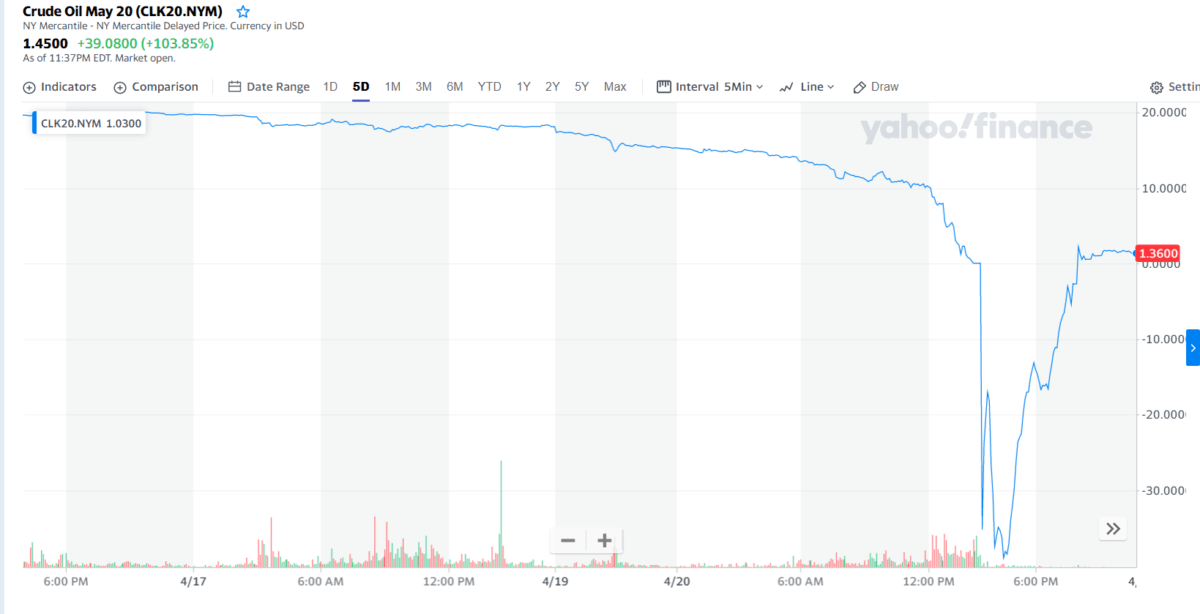

Oil futures contracts for May expiry recently traded at -$37 a barrel in April 2020. How is that even possible? To answer this question, you need to have context.

There are multiple measures and metrics in the field of trading oil. One metric is called physical price, which you can buy oil in physical markets for delivery to your refinery or terminal. The physical price is sixteen dollars for an oil pricing benchmark called WTI and twenty-two dollars for another benchmark called Brent. (See making sense of energy markets.)

Then there is paper price. The price at which you can buy oil in financial market sometimes without taking delivery, sometimes with delivery.

A deliverable contract requires you to take delivery of physical oil, ship it and store it where you can use it. But what if global demand has crashed, supply still hasn’t adjusted and you are out of physical storage. Paper oil works well if you don’t have to take delivery. Under normal operating conditions you can always find buyers for your paper contract who are happy to take delivery. Unfortunately April 2020 wasn’t normal.

What happens to the price of oil then? If there are no buyers of oil, you need to give an incentive to people to store it. That is where the -$37 price tag came from.

How do you make sense of this world? If you do not understand context and try and model trends you will end up as a Shakespearean tragedy.

Models are tricky because data is tricky. Context is important because it allows us to understand and model the curves data may throw at us. Context also give us the right questions to ask. You cannot have context without studying history. If you want to build models, study history for context. Not just history of models but the history of mistakes and wrong turns. Explore conflicting and contradictory views.

The big money in models is not in models. It is in intuition.

It is in understanding data, connections, relationships, and insights behind data.

If you have intuition, and you do not know how to code, I can give you programmers that you can work with. But if intuition is missing, I cannot teach it.

Where does intuition come from? Intuition comes from being wrong. Intuition comes from building models for years till you get a sense of what works and what does not work. When things fit and when things do not fit.

If the value is in building intuition and in being wrong, what should you focus on?

The more wrong you are, the more wrong you have been, the more wrong models you have under your belt, the more valuable you are as a data scientist, as a modeler, as an ML and AI specialist. Because you understand what breaks model and you can account for it.

Lesson four. Relative value and insight.

How do you know when something is overvalued or undervalued?

Twenty years ago, how many Honda Civics would it take to buy a detached single family home in a respectable neighbourhood in your city?

Here are the numbers for my city. A thousand yards square yards plot in Defence (DHA) in the year 2000, would have cost you PKR ten million (USD150,000). A Civic would cost you PKR one million (USD15,000).

About ten Civics for a thousand-yard plot or a single-family home. In 2020 the same plot of land is worth 100 million (USD700,000). A Honda Civic costs PKR four point two million (USD26,000).

Which one is overvalued? The land or the Civic?

In dollar terms over the last twenty years land appreciated 5 times. Civics were not as lucky. Hence the change in ratio. Today to buy the same land you would need 29 Civics. Three time as much as you needed twenty years ago.

Does that make a Civic a good buy? Not if you are looking for a home to live in or invest for the future. Does that make land over valued? Not necessarily since we are comparing apples to oranges.

Relative value is a powerful tool, but we need to begin with the right comparisons. Like with likes or near substitutes. We often use the tool but compare Civics with single family homes. Both are valid consumption choices but are not comparable or near substitutes.

Let me ask a different question.

What was your yearly fee tuition fee at a top tier university in your country for your undergraduate program?

Once again here are the numbers for my city. If you went to top ranked private university in 2020 in Karachi, you need to put aside USD 8,000 per year for tuition plus other expenses.

What was my yearly fee when I started studying CS in the 90’s? USD 400 per year plus expenses.

Within thirty years, tuition fees have grown twenty folds in dollars terms and over a hundred-fold in local currency terms. Here is the question I really want to ask.

Has the quality of your education improved a hundred times?

A good test for this answer is compensation. If the quality of education has increased twenty-fold in dollars some of that improvement must reflect in compensation levels expressed in dollar terms.

My starting salary as a freshly minted computer science graduate was USD 250 a month. I could earn back the amount invested in three years of my education on a pay check within six months.

What is the average compensation today for a similar resource? USD 400 a month.

What was it twenty years ago? USD 200 a month. 10 years ago? USD 500 a month.

What is the average breakeven time on your education investment today expressed in years of employment? 5 years at 500 a month, 6.6 years at 400 a month, 10 years at 250 a month.

While tuition fees have increased twenty-fold, compensation has merely doubled in good years and the breakeven time has increased ten folds. It is not looking good for the quality of education debate.

How do I know? Because I have been a teacher for twenty-five of those thirty years.

In 1990 in our three-year program in CS, we simulated the 68000 processors at the microcode level, wrote an operating system for it, wrote a compiler for C in C, built a neural network, a line detection tool and researched the cost of query execution in SQL. These were just six projects for six of our thirty core courses. We did all of this on 64kb of RAM without access to stack exchange, the internet, visual IDE’s, torrents to download books we needed, or high-speed processors.

While my students today are more blessed, smarter and shaper than we ever were, head to head, I think we would be leaner and meaner. Certainly, standards of living, discretionary income, employment opportunities have improved in thirty years. All of that cannot negate the fact that the quality of education has not kept pace with the rise in tuition fees.

Now for the head fake I was leading you to.

I hope you realize that all the analysis up to this point is flawed. I leave that to you to figure out the flaw in my argument.

Relative value is a framework. Comparing single family homes with Civics or cost of education with compensation trends or breakeven period is a model. Understanding that both are fundamentally flawed comparisons is insight.

Without insight the first two are worthless.

Lesson Five. Optionality.

What is optionality?

Optionality is spending a little bit more so that you have more flexibility when faced with uncertainty in future. Optionality has a price. Rarely do you get it for free. It is more common to pay for it. Sometimes optionality is priced fairly, more often you end up paying an arm and a leg for it (think extended multi-year warranties on electronics purchased at your local store – great idea for the stores, terrible idea for the consumer).

Optionality is flexibility. Flexibility becomes important when you are faced with uncertainty. How important is flexibility?

Let me illustrate with an example we can all relate to.

In early March, eight weeks ago, we shut down universities and workplaces and sent everyone home because of Covid-19.

We said we will work and teach from homes. To do that one needs to meet certain requirements.

The first is a decent broadband connection. Second, reliable electricity. Third, a decent laptop. If you are teaching, studying, or working, a quiet area where you can work through six to eight hours a day without being disturbed. Fourth, if you teach or spend a lot of time in meetings, a podcast quality microphone.

If you had all this, you could go from your old world, an office centric, instructor-led classroom model, to a new world, a no contact, remote meeting / remote learning model.

If you did not you had to scramble to equip yourself with tools, and facilities you were not used to in your prior life.

I had a quiet room because I often work from home. I have a fast internet connection because I need it to retain and maintain my sanity. I have a laptop because we learned the value of portability and not being dependent on the electrical grid or generators due to decades of power load shedding. My last laptop did not have a webcam but my current one does. I got exposed to online training in 1999 as an instructor. I hate it compared to live classroom instruction but in the absence of other options I can live with it.

If I did not have any of the above elements, I would not have the flexibility to teach online. I know colleagues who are struggling with the new model because it is alien to their way of teaching and working.

Optionality is not always this explicit. Sometimes optionality means that you spend a little extra, you do a little bit more. A tiny bit of extra effort, so that when the time comes for you to walk in a different direction, you have an option.

When is optionality valuable? Optionality becomes valuable when uncertainty increases.

The university I teach at switched to emergency remote learning at two weeks’ notice. Our initial reaction was campuses will re-open in June. But just in case we do not, let us experiment with this new model now. Put in the effort and test it out. Sort out the bugs, tweak delivery, access, and reach issues for students and faculty. Just so we have a credible option in June if the lockdown in extended.

Come May, we know the academic lockdown has been extended. We did not know that in March. We hoped for the best, but we were not sure. But now in June, we have a credible option. Because we put in a bit of extra effort in March.

Optionality, uncertainty, and flexibility. The three work very well together.

Another way of handling uncertainty is to take small bets. Incremental risks that you take to gain future flexibility that may not cost a lot in the beginning but stack up over time.

I often pose this question to my students.

When faced with an important configurable variable for your enterprise application is it better to store it in a database table? Or keep it in memory? A configuration parameters table or a memory variable, read from a configuration file every time the application is executed.

The first requires a bit of extra effort and maintenance, the second is a low cost functional option

We once had fifteen such parameters that we needed to store. What did we do? What would you do?

We were building a calculation engine. The fifteen very quickly grew into three hundred. Luckily we had decided at inception to go with data base tables rather than memory-based variables or a simple text based file. The configuration tables required extra work but gave us the option for a flexible design if the variables grew or if the rules controlling them changed. Queries had to be written and the database design was modified. There was a bit of grumbling, but we did it.

By the time we were done four years later, there were two thousand parameters that had to be stored and set. By exposing them through screens and linking them with user profiles we made it possible to batch generate a deck of two hundred reports against a standardized set of stored parameters. You could set it up to run at night and go home. When you came back to work in the morning the deck would be done.

The standardized deck was faster and more efficient than setting two thousand parameters by hand for a large bank. And since you could only run this after the day end was done, having the option to run it overnight as a standalone process was a star feature for our customers.

Even bigger payoff came when we moved markets and the rules governing these variables changed. Rather than digging into code we could extend our user profiles into national profile. An implementation in a different country would not require us to touch code. All we had to do was to identify which rules were different, change the relevant parameter, test results, send the revised reports for client validation and were good to go without leaving the confines of our offices.

Optionality. Invest a little extra effort so that you have flexibility on your side when faced with uncertainty.

Special note: If you are interested in optionality you must investigate the relationship between optionality, convexity and uncertainty. Together the three represent the most powerful concept in all of finance. Nicholos Nassim Taleb (NNT) has written a great deal about this topic in Fooled by Randomness. Look up the book if you haven’t read it as yet.

Lesson six. An idea is a network. Using networks to scale.

Steven Johnson in Where good ideas come from poses a powerful concept.

An idea is a network. As you expose ideas to different people, the value of the idea increases. When you bring an idea to an existing network of people you are not just adding a node, you are adding an entire network. Metcalf’s law indicates that the impact or value of a network is n^2 (n raised to the power 2). When you merge two networks you increase value many times more than just the sum of their nodes.

Specialization take time to build. Networks also take time to build. You do not have to build them in sequence, you can build them in parallel. When the time is right you bring them together.

What comes first? Specialization. Then comes scale. Specialize first then scale. Use the power of networks to scale faster.

Lesson seven. Fixed costs.

How much does an Airbus A380 costs?

This is the baby elephant airplane that flies with two full decks and four engines. It costs roughly US$ 700,000 a day to operate. Can accommodate as many as 860 passengers in a single class (economy only) configuration or 550 passengers across three classes (economy, business and first).

Sticker price. Four hundred and forty-six million dollars. US$ 446,000,000.

Significant discount if you are buying in bulk or represent one of the largest airlines on the planet. But even with discounts and leasing costs spread over 5 years, you are looking at operating costs in the million dollar a day range.

How many A380s does Emirate airline have? How many did they buy?

One hundred and fifteen aircrafts as per public records. What is that fleet doing right now? They are sitting on the ground gathering dust at Dubai airport. Yes, they are parked because the airline and travel industry is still trying to sort out the mess that is Covid-19.

If they are parked how are they generating a million dollars a day in revenue? Revenue that they need to break even.

Ignoring fuel and crew costs, you are looking at $250,000 a day to $500,000 a day in fixed costs that Emirates must bear. It does not matter if the aircraft flies or not, this is money that the aircraft burns while sitting pretty on tarmac. Think of it as rent that is due at the end of the month whether you use the office or not.

US$ 250,000 per day into one hundred aircrafts is twenty-five million dollars a day, seven hundred and fifty million dollars a month. I do not even want to think about what it would cost over a year. That is just the A-380 fleet. Emirate also has a equally large fleet of Boeing 777s burning another hole in the ground.

Meet the curse of fixed costs.

If your business is on hold because of Covid-19, if you are not serving customers and are operating in work from home mode, what would it cost you to exist? To survive? Every business has some element of costs that must paid whether you are open or shut, closed or open. Rent, interest and lease payments, baselined utility bills, local taxes, compliance, licensing, filing fees and salaries for crucial staff.

Higher your fixed cost, lower your ability to handle uncertainty. Lower your ability to handle shocks to the system.

Is the airline industry alone in the world of high fixed costs.

This is the Four Seasons at Koh Samui, in Thailand. Do you think it is any different from an airline fleet of grounded aircrafts?

Even without serving a single guest, the Four Season at Koh Samui needs to spend a tidy bundle to survive and exist. The list of expenses for a property with such a profile is endless. Just so it is around when the world opens to discretionary recreational travel again.

High fixed costs are bad news for businesses in trouble. High costs are bad news for businesses when things change without prior notice. High fixed costs are a challenge in times of uncertainty. Why?

Because high fixed costs restrict your ability to respond. They reduce your flexibility. Think carefully before you add fixed costs to your business.

Bonus Lesson. Marginal costs.

I sell study guides, online courses and excel templates. My fixed costs for running and hosting the site are already allocated and accounted for at current sales levels. What is my incremental cost for serving one additional customer, processing one additional order, shipping one more guide?

Since most of the materials are digital, one would think zero. That is not true since they are monthly variable costs associated with the shopping cart, the payment aggregator and addressing customer questions and queries. Once they are accounted for the numbers are still quite low when compared to shipping print editions of the same guides.

Product focused technology businesses often have low marginal costs. Services focused technology businesses have higher marginal costs. Product businesses may have higher notional fixed costs if they have allocated a portion of their research and development costs to future sales. If they do, marginal costs may be higher; if they do not, lower.

Successful businesses that dominate their segments and have low fixed costs and low marginal costs are rare. Low marginal costs often require scale which requires capital investments which imply higher fixed costs. Low fixed costs and high variable costs are more common in early pre-scale stages as founders have limited capital to invest in infrastructure and manufacturing capacity.

Post scaling if you still have high fixed costs and high marginal costs, your business is inherently broken and is likely to run into trouble in the next downturn.

While each sale should contribute its allocation of fixed and variable costs, there are instances when serving an additional customer may represent lower than normal marginal costs. Not just in technology businesses but also in traditional brick and mortar enterprise. Last minute ticket sales, hotel room discounts and marked down near expiry Marks and Spencer mini chocolate bites are great examples.

Low marginal costs make it possible for you to:

- Respond to competitive pressure by lowering prices temporarily.

- Increase the demand side by playing the volume game by reducing prices permanently, or

- Given incentives to customers to try products through free trial periods or free giveaways.

Keep your marginal costs low if you want to compete in hard times.

Conclusion and takeaways

We have barely scratched the surface of finance. Each of these topics is a lecture by itself. Reading a book on these topics or hearing one speak about them is not enough. You need to practice these lessons as frequently as possible.

Sunk costs and fixed costs are especially difficult to internalize. It is only when you are bitten by them and end up losing a business on their account that you understand.

Of the seven, optionality and using networks to scale are the two most powerful ideas I have come across in the world of finance. If you remember any two of the above, remember these two. If you want to explore any of the above, explore these two.

Additional Readings

Sources and references

- https://financetrainingcourse.com/education/2017/07/innovation-lessons-startups/

- Option Greeks Primer, Jawwad Ahmed Farid, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.